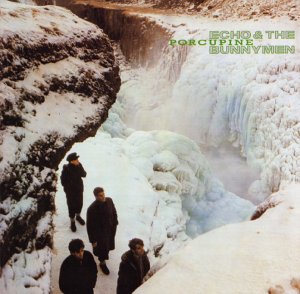

FOREWORD: Working class post-punk Liverpudlians, Echo & the Bunnymen, were part of the ‘new psychedelia’ movement local antecedents, the Teardrop Explodes, helped fortify with ‘80s universally acclaimed Kilimanjaro. Guitarist Ian Mc Culloch had been in the Julian Cope-led Crucial Three before Cope started up Teardrop Explodes. But Mc Culloch split and went on to find success leading Echo & The Bunnymen, whose exceptional debut, Crocodiles, maintained an eccentric cleverness captured best on suspenseful Brit smash, “Do It Clean.” Though ‘81s middling Heaven Up Here further secured an enlarged cult status, it was ‘83s lissome goth-gloom masterpiece, Porcupine, with its stark symphonic sharpness and icy violin crescendos, that secured aboveground acceptance inside and outside Europe. ‘84s equally compelling, magnificently orchestrated Ocean Rain, replaced any leftover macabre apparitions with a confident melodic splendor.

After a three-year layoff, ‘87s self-titled fifth album produced the pop schlock dandy, “Lips Like Sugar,” while ‘88s Pretty In Pink movie soundtrack offered finely-detailed moody retreat, “Bring On The Dancing Horses.” But Echo & the Bunnymen were temporarily halted while Mc Culloch went solo with worthwhile ’89 LP, Candleland.

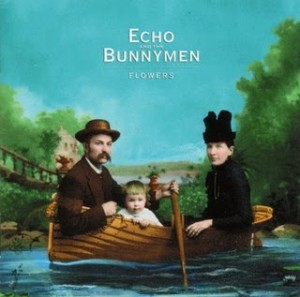

Despite reuniting for ‘90s brooding Brit-pop mediocrity, Reverberation, Echo & the Bunnymen once again withdrew, waiting seven years before the valiant comeback, Evergreen. A steady stream of average-to-good LP’s followed, including ‘99s What Are You Going To Do With Your Life, ‘01s Flowers (which I promoted with the Ian Mc Culloch phone interview below), ‘05s Siberia, and ‘09s The Fountain. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Ever since the late ‘70s punk explosion, Echo & the Bunnymen have possessed an artful quirkiness and stylish Romanticism that countered the primal, raw virulence of first wave reactionaries the Sex Pistols, The Clash, and the Dead Boys.

Lead by rhythm guitarist Ian Mc Culloch, a debonair singer with a piercing caterwauled wail, and lead guitarist Will Sergeant, these gothic Liverpool-based post-punks helped invent a ‘new psychedelia.’ Boasting a more informed, sophisticated, and formal approach than its roughhewn competition, Echo & the Bunnymen soon became one of England’s greatest ‘80s bands.

The baroque grandeur and majestic orchestral drama of ’80 debut, Crocodiles, and ‘81s less intriguing Heaven Up Here ushered in the visionary breakthrough of ‘83s gorgeous Porcupine (featuring the throbbing evocation, “The Cutter”) and ‘84s arguably better Ocean Rain.

After a self-titled ’87 album assisted by former Doors keyboardist, Ray Manzarek, Mc Culloch went solo for ‘89s plaintive beauty, Candleland, and its worthy follow-up, Mysterio.

Re-formed and reinvigorated, Echo & the Bunnymen came back strong with two more lushly textured albums: ‘97s mood-struck Evergreen and ‘99s difficult-to-find What Are You Going To Do With Your Life.

Still searching for salvation in a world offering little spiritual guidance, the liquefied guitar swirls and billowy synthesizer smoothness of ‘01s promising Flowers offered further evidence of Mc Culloch and Sergeant’s combined genius. From the glistening curlicue guitar feedback of the faith-riddled “King Of Kings” to the tongue-in-cheek sarcasm of “Everybody Knows” to the glimmering vibes and backward tape loops of “Make Me Shine,” Flowers may be the most exhilarating step forward yet.

Still searching for salvation in a world offering little spiritual guidance, the liquefied guitar swirls and billowy synthesizer smoothness of ‘01s promising Flowers offered further evidence of Mc Culloch and Sergeant’s combined genius. From the glistening curlicue guitar feedback of the faith-riddled “King Of Kings” to the tongue-in-cheek sarcasm of “Everybody Knows” to the glimmering vibes and backward tape loops of “Make Me Shine,” Flowers may be the most exhilarating step forward yet.

Though their music hasn’t changed much since the elegiac provocation, “Do It Clean,” they remain seminal figures of the underground rock scene.

I spoke to Mc Culloch for a half-hour via phone.

Who were some of your formative musical influences?

IAN: The first thing that floored me was David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust. Then I went back and got Space Oddity and Hunky Dory – which is now my favorite Bowie album. I couldn’t wait for his albums to come out. They kept me sane and insane and got me through that weird time between ages 13 and 15 when all I cared about was football and Bowie. It made me want to be a singer. He’d mention in interviews Velvet Underground, Iggy Pop, and Jacque Brel as influences. That sounded intriguing so I got hooked on them.

Then the Doors came later through Will. He’d play their stuff and I’d think ‘this is the missing seed in the pack.’ I love Leonard Cohen. I consider him part of the lineage or family tree from Bowie. I always liked the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Kinks. But I was more fascinated with the more decadent, dark songs by the Doors, Lou Reed, and Iggy & the Stooges. I always looked for that atmosphere in music.

Were you an original member of fellow post-punk Liverpool band, Teardrop Explodes?

IAN: I wasn’t. There was one time when the band was called Shallow Madness. I was meant to be the singer because I suppose I looked the most likely for the part. But the music wasn’t the kind I wanted to do. Therefore, I didn’t show up for many rehearsals even though they were held in my flat. I’d disappear the night before. I was too shy to sing; too shy to tell them. They got fed up with me, and Julian Cope started singing.

The Bunnymen’s first few albums dealt with heavier topics such as politics, depression, and agony. Over the years, your lyrics became more reflective and personal.

IAN: That started when I made two solo records. After that, I didn’t want to go back. Early on, it was more metaphysical and existential. Then I realized the songs that touch you more are more personal, like Bowie’s “Changes” and “Heroes.” His most personal record, Hunky Dory, sounded like a bloke with a guitar rather than a bloke from outer space. What I wanted to get across was that one to one, when a line hits you. The early albums skirted around those things. It was more superficial angst than personal lyricism.

What do you like best about the way Flowers turned out?

IAN: The warm, affected guitar sounds are quite clear and crisp. There’s not layers and layers of things going on – which I may have been guilty of in the past. We became aware how it sounded like Crocodiles more than any of the others. Also, there was a touch of the Doors first album with the guitar affects. You just go instinctively for what you fancy.

I heard it cost less money to make Flowers than it did to record Crocodile over twenty years ago.

IAN: We never spent fortunes. You could spend months unnecessarily. This was written and recorded with Will’s main guitar lines in twelve hours. Over the course of a month, he’d come around for two hours and we’d come out with four basic songs or the beginning of a song. We’d be like, “Wow! We’ve got six songs now.’ That didn’t include lyrics, but the basic melody lines were going well. We thought it would take ages for the rest of the band (keyboardist Ceri James; percussionist Vincent Jamieson; and bassist Alex ‘Kong’ Germains) to feel comfortable, but they found it easy to come up with spontaneous bits at this funky little fourth floor floorboard studio with big windows opposite an old police station in Liverpool.

I’m not yet familiar with the previous album, ‘99s What Are You Going To Do With Your Life?

IAN: It’s the closest in sound to Ocean Rain in terms of songwriting style. It’s very orchestrated. It’s hard to tell with Will, but I think it’s the album he’d have liked more if it were a solo album by me. His involvement wasn’t that great. It’s acoustic based in the main but with lots of strings. Most people don’t know it’s around. It shows how bad the previous record company people were. People who’d been with us since 1980 had no idea of its existence.