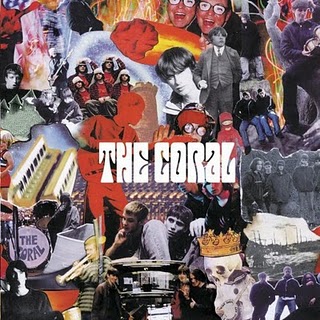

FOREWORD: I got to hang out with British pop idols, the Coral, during their first American tour supporting ‘02s rewarding eponymous psych-folk mod rock debut. Stargazing guitar group revivalists, the Coral went on to reach number one in England with respectable sophomore set, Magic And Medicine, but were jilted by US lack of interest. I’m unfamiliar with ‘04s The Invisible Invasion and ‘07s Roots & Echoes (which wasn’t released in the States). Lead singer-guitarist James Skelley proved to be a rather shy, soft-spoken person offstage. But the rest of the band was more outgoing. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Onstage at Manhattan’s crowded Mercury Lounge, Britain’s latest press darlings, the Coral, prove worthy impressing stateside informants through the relentlessly frenetic sea shanty opener, “Spanish Main,” to the distended Searchers-obliged closing mantra, “Goodbye.” Musically sophisticated beyond their years (ages 18 to 21), these cleverly resourceful thick-accented Merseyside villagers shun post-punk conventionality by dousing intricate arrangements with crusty Yardbirds-styled riffs, twanged surf rock borrowings, psych-garage organ motifs, and doo wop-influenced harmonies.

Now proud college dropouts, Hillbury High pals James Skelley (vocals-guitar), his brother, Ian (drums), Nick Power (organ), Bill Ryder-Jones (guitar-trumpet), Lee Southall (guitar), and Paul Duffy (bass-sax) have garnered massive UK media attention since their self-titled debut sold an impressive 100,000 copies in Great Britain alone.

Whether chanting simple nursery rhyme schemes on the nifty “Simon Diamond,” drifting into the reggae-fried “Dreadlock Holiday” abyss of organ saturated “Shadows Fall,” or slipping through scampered Madness placation’s such as the soulful “Dreaming Of You,” and the anxiety-riddled “I Remember When,” the Coral consistently scramble jumbled influences in intentionally awkward ways.

Whether chanting simple nursery rhyme schemes on the nifty “Simon Diamond,” drifting into the reggae-fried “Dreadlock Holiday” abyss of organ saturated “Shadows Fall,” or slipping through scampered Madness placation’s such as the soulful “Dreaming Of You,” and the anxiety-riddled “I Remember When,” the Coral consistently scramble jumbled influences in intentionally awkward ways.

Perhaps the most inextricable illustration of their deranged diversification comes via the spasmodic “Bad Man,” a frazzled espionage-themed elixir with fluctuant time signatures, sinister clipped guitar clusters, and burbling wheeze-box undercurrent.

Are the Coral part of a thriving Liverpool-based scene?

BILL: It’s going through a transition and turning itself around. It’s a bit of a positive place to come from. It still has its flaws. Local bands like the Bandits, who are into ska-skiffle sounds like the Clash-meets-the-Sex Pistols. The Stands are more like the Byrds’ Sweetheart Of The Rodeo country-folk.

PAUL: Then there’s two lads called Hokum Clones that do bluegrass ragtime with two acoustic guitars. The Irish band, Zutons, is on our label. When we started getting into music, we weren’t serious at fourteen years old yet. The band Madness was cool.

LEE: At that stage, you’re not sure what you’re into. The bands we initially liked were the Beatles, Oasis, and the La’s. The La’s made the best pop songs of the ‘90s. We’ve been playing some of our songs for four years, so the problem becomes ‘How do you play the songs with the same feeling?’

How do your diligent arrangements usually come about?

BILL: Most songs are collaborations that are created out of chords. It’s not really a set way. We go over what the feel of the song is and it comes together.

LEE: We could write a few lyrics and put two chords together and a whole song comes out of it. It’s just us.

Your closing song at the Mercury Lounge gig, “Goodbye,” was stretched out live. Its stinging leads reminded me of the Yardbirds while the harmonies

seemed influenced by the Searchers.

PAUL: We like to freak out on that. It’s completely selfish and indulgent. We just like to jam out.

The obtuse “Skeleton Key,” with its Captain Beefheart-skewed rhythmic complexity, nearly resembles the music of the New York City band with the same name.

PAUL: There’s also a band named Shadows Fall.

On that song, “Shadows Fall,” you play a reggae bass line.

PAUL: To be honest, I was on vacation when they wrote that song. It’s not just standard reggae. It skips through styles. The words Nick wrote and the theme called for that bass. But it wasn’t premeditated.

Nick, what’s the inside scoop concerning the lyrics to your song, “Simon Diamond”?

NICK: It’s kind of tragic. At the end of the song, he changes into a plant. He has arms to wash himself, but he can’t because he’s a plant. It’s philosophical. Sometimes you sing the chorus until it fits into your liking and that’s the essence of it. Sometimes, they’re made up on the spot.

Are you into Northern Soul?

NICK: That’s what we’ve always done. We listen to everything. But we’re so bored because there’s so little to do where we live, so we sit in our bedroom. There’s a high population of old people. So you have to amuse yourself in some way. The first thing I got into was Bob Marley. Then, there was John Lennon and Bob Dylan. They’re the biggest icons. I also like Captain Beefheart and Scott Walker.

The neo-orchestral parts on some songs are reminiscent of Scott Walker’s early ‘70s singer-songwriter stuff.

NICK: It’s never preconceived how we’re gonna write. We get an idea, go into the practice room, then whatever happens…you chuck a load of ideas around. If you’re in a band and you’re getting paid for it, you should get everybody involved.

How’s the second record coming along?

JAMES: It’s more refined than the first. The quality of songwriting and the arrangements are better and we’re better players now. It’s more within one mood. It’s not as chopped together as the first was.

NICK: The parts of the debut you hear that you can’t relate to any other band is what the whole of the second album is like. It’s more like in ten years time it’ll have a more obvious sound. Our first album was a great, weird representation of where we were then. The next is a more of a mood album like one of those thematic Hawaiian albums that take you someplace else. It’s like the quiet after the storm with some severe Can jams.

(The interview moves downstairs to the Mercury Lounge basement area where James Skelley confides)

I notice your vocal arrangements seem influenced by the purity of doo wop.

JAMES: Doo wop is rock and roll, isn’t it? Just like Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers and “Red Sails In The Sunset” or the Spaniels or the Impressions. It’s all feel-good music. I think those were the things I was into, but now everybody in the band is into it.

Did you and your brother, Ian, grow up in a bohemian household with creative parents?

JAMES: No. They were just never really in. They were always out. There was no one to tell us what to do. My mom got into the Beatles, Stones, Small Faces, the Kinks, the Who, and David Bowie. But they were into shit music as well. However, they were also into soulful American artists like Jackie Wilson, Smokey Robinson, and Sam Cooke. And stretching back before that, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, the Ronettes, the Teddy Bears, and “Mr. Sandman” by the Chordettes. Bo Diddley is future music. There’s been nothing as contemporary as Bo Diddley since.

Where do you draw lyrical influences?

JAMES: Bob Dylan, Smokey Robinson, Lennon-Mc Cartney, Arthur Lee and writers Dylan Thomas, William Wordsworth (Tintern Alley), John Steinbeck (The Grapes Of Wrath).

So you have quite a few literary influences?

JAMES: Yeah. I got The Old Man And The Sea and I just started reading stuff like Tom Sawyer.