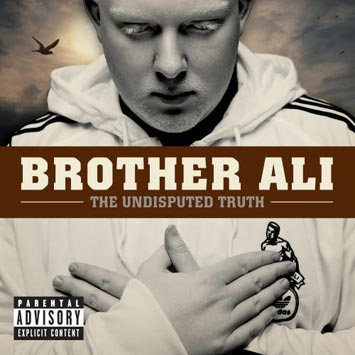

Brother Ali, a highly regarded music hustler informed by old school hip-hoppers KRS-One and Rakim, relates tales of troubled youth on fascinatingly detailed magnum opus, The Undisputed Truth. Victimized at the hands of an immaturely irrational society unconscionably ill-equipped to deal with anybody deemed too weirdly preternatural, the pigmentation-challenged ghost-faced north-westerner seeks affirmation on his own terms. Contradicting the misconceptions aimed at a bald buck who’s a whiter shade of pale, the enterprisingly emancipated emcee peddles a tremendous cross-section of rap, soul, rock, and folk not completely dissimilar to black-busting honky bonkers Everlast or Aesop Rock.

Brother Ali, a highly regarded music hustler informed by old school hip-hoppers KRS-One and Rakim, relates tales of troubled youth on fascinatingly detailed magnum opus, The Undisputed Truth. Victimized at the hands of an immaturely irrational society unconscionably ill-equipped to deal with anybody deemed too weirdly preternatural, the pigmentation-challenged ghost-faced north-westerner seeks affirmation on his own terms. Contradicting the misconceptions aimed at a bald buck who’s a whiter shade of pale, the enterprisingly emancipated emcee peddles a tremendous cross-section of rap, soul, rock, and folk not completely dissimilar to black-busting honky bonkers Everlast or Aesop Rock.

Legally blind albino, Brother Ali (born Jason Newman, 1984), now a devout Muslim, has continued to struggle against many unjust foils. Misunderstood by childhood peers, beat up in high school, once divorced, sporadically homeless, and probably stronger emotionally, if not physically, from all the lowdown hard times, the well-versed rapper somehow managed to keep a cool head. Originally from Madison, Wisconsin, Ali settled in the humble confines of Minneapolis by age fifteen. Fortuitous meetings with Ant and Slug, semi-famous mainstays of bona fide underground hip-hop duo, Atmosphere, cleared the way for the visually impaired pale-faced jabber.

Though he admits to loving Eminem’s “real,” as opposed to “fantasy-related” rap, Ali’s main influences are clearly African-American, whether Rhythm & Blues veterans or Jazz luminaries. His husky coal-stained baritone, redolent of super ‘70s soul singer, Joe Simon, retains a thick-skinned assertiveness. Having been pushed around as a juvenile, he soon found solace with the black homeboys more so than the less accepting white kids who’d oft-times give him strange looks.

Initially, he impressed throngs at the 2000 Scribble Jam Festival rap battle. Soon, Ali’s well-received demo cassette EP, “Rites Of Passage,” doubtless a self-portrait, got the ball rolling. Rhymesayers Entertainment entrepreneur, Slug, quickly befriended him, eventually signing the chunky red-eyed wordsmith to his flourishing indie label.

Astonishingly, he gives big-ups to early Blues legend Son House and ace ‘60s soul star Syl Johnson, but admits, “I’ve had to start over so many times in my life that my record collection is shit. But I collect it in my head and I have friends whose records I borrow.”

Brother Ali’s articulate flow commands attention, whether divulging personal matters of the heart, flaunting common sense righteousness, or spewing ill-willed condemnation aimed at evildoing haters (a favorite rap subject). Usually, his sharp-witted, choppy rhyme scheme goes against the penetrable clap-tracked rhythmic thrust. Now remarried with a son, Faheem (from his first marriage), he admits the Muslim community “has its problems,” but respectfully believes the holy scriptures convey a positive message beyond religious affiliation. And this faith instructs his entire muse.

‘03s psychoanalyzed showdown, Shadows On The Sun, opened some more doors, exposing Ali to a limited national audience. Still ridiculously overlooked (by the masses anyway), ‘07s strikingly gritty breakthrough The Undisputed Truth, dangles valiantly sociopolitical outrage above nastier gangsta leanings. His rapid-fire elocution deepens resolve on testier fare. Raging dragon slayer, “Lookin’ At Me Sideways” confronts the sinisterly confounding resentment he’s faced and obviously takes umbrage at. Investigative verity, “The Truth,” huffs its slumming ghetto demand ‘til jailed Bronx rapper, Slick Rick, utters some whack gibberish before poignantly admitting sometimes ‘the truth is detrimental’ at the disturbingly defeated finish.

Though not as dangerously rampaging, “The Puzzle,” with its sped-up squirrelly chorus about ‘the state I’m in,’ easily holds up next to brash skull-bangers Public Enemy and Boogie Down Productions. Clever retort, “Pedigree,” slams disbelieving rivals, as slack guitar-bass rhythm, punctual car-horn toots, and soulful female descants garnish boastful dispatch: ‘your pedigree don’t hold up to mine/ I’m a thoroughbred.’

He ain’t afraid to get religious on your ass, either. Dedicated to the prophet Muhammad, “Daylight’s” sharp intermittent brass crosscuts ‘70s blaxploitation drama as distant Gospel singers unceasingly wail a sunshine-y refrain and our reluctant hero laments ‘you have no idea how to frame me.’

Then again, Ali’s not scared to get stylish, draw upon similes, or make a grand statement. A truncated reggae groove sets the stage for orchestral curb, “Freedom Ain’t Free,” and indignant broke-down depression, “Letter From The Government,” makes an analogy paralleling Iraqi war vets to urban street soldiers. Similarly, laid-back hick-soul complaint, “Uncle Sam, Goddamn,” protests America’s prejudicial bureaucratic injustice in a mannered repartee reckoning ‘70s-based rap antecedents, the Last Poets, bemoaning, ‘welcome to the United Snakes, land of the thief, home of the slave.’

“I made a cheap thousand dollar video for “Uncle Sam, Goddamn,” which got played all over the place online then got me in trouble with homeland security,” Ali says. “It got me kicked off the tour by the corporate sponsor. It was right around the time Akon got kicked off the Gwen Stefani tour. The sponsors who made a lot of money off rap had too much say over what you can do. It happened with Pepsi and Ludacris beforehand. That was a trend.”

But Ali’s not all about the bad times. The nostalgic “Listen Up” is a minimalist ass wiggling ‘bang bang boogie’ party jam reminiscent of early Beastie Boys and Run DMC – with a testifying deacon breakdown for good measure.

But ultimately, the best cut has to be bangin’ car tune, “Take Me Home.” Its easy groovin’ off-the-cuff flow rides atop punchy bass drum and snare as a liquefied blues-y guitar saturates the folksy verses. The straight-up positive-minded anthem should’ve set the world afire.

“Guitarist Jef Lee Johnson (celebrated Philly psych-funk session man) was playing in a Paris-based free Jazz group that came to Minneapolis. I ended up joining that group. Afterwards, Jef came into the studio and played guitar on everything. At times, I didn’t know what to do so I just free-styled, sang, did beatboxing, and told stories. Based on that, we got a bassist and keyboardist. “Take Me Home” benefits from that. There’s still samples, but the instruments give it more texture.

Regarding the accumulative affect of The Undisputed Truth, Ali claims, “I was hoping to make it a cross-section and reach out to people who otherwise wouldn’t listen. We spent more money on one video than the album. But overall, I’d say I’m satisfied.”

In the end, Brother Ali’s perseverance paid well-earned dividends. Looks like the future’s bright ahead.