Overcoming extreme adversity and a healthy dose of animosity, proggy Texas-sprung hardcore experimentalists, And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead, have picked up the pieces and moved on. Fully revitalized and free from major label concessions, they’ve returned strong with the mindful self-released reclamation, The Century Of Self.

Overcoming extreme adversity and a healthy dose of animosity, proggy Texas-sprung hardcore experimentalists, And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead, have picked up the pieces and moved on. Fully revitalized and free from major label concessions, they’ve returned strong with the mindful self-released reclamation, The Century Of Self.

Formed by two waywardly kindred souls determined to forsake Hawaiian ‘island fever’ by going inland, Trail Of Dead’s Conrad Keely and Jason Reece soon trekked to Olympia, Washington, playing in local bands until the nearby Seattle scene, once internationally revered, went cold.

After the grunge phenomena faded and provincial mentor Kurt Cobain committed suicide, a dark cloud hovered over the Pacific Northwest. According to Keely, “doom and gloom hit so hard many bands moved away.” Keely and Reece took residence in musical hotbed, Austin, Texas, perusing the vibrant coffeehouse scene benefiting dozens of native bands.

Born in the United Kingdom, raised in Thailand, and uprooted to Hawaii, Keely received a long musical tutelage in Washington. While there, Keely witnessed the impending grunge scene firsthand, catching a badly attended local show featuring the Melvins, Beat Happening, and the soon-to-be-ubiquitous Nirvana during 1988. This exposure to the burgeoning cultural phenomena in Seattle provided plentiful stimulus for his inevitable endeavor.

And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead, whose protracted appellation was snatched from a Mayan ritual chant as a reactionary response to one syllable contemporary bands such as Blur and Hum, came into fruition quickly in the Texas capital. Joining the fray were guitarist Kevin Allen, bassist Neil Busch (replaced by Danny Wood, then Jay Phillips), and drummer Aaron Ford.

An incredible live band apt to wreak havoc, break instruments, and overwhelm audiences, Trail Of Dead eventually signed to Merge Records, blowing away audiences while opening for renowned Carolina indie combo, Superchunk.

Lacing prog-rock intricacies into energized punk assaults, ‘99s astounding Madonna proved to be an expert blend of metallic guitars, symphonic explorations, and psychedelic intrigue that went far beyond generational post-grunge angst. Perchance a spunky response to Cobain’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” satirical hard-driven rampage, “A Perfect Teenhood,” is an explosive fuck-off with a disconcerting meltdown utilizing the same fast-loud choruses and slow-soft verses Nirvana indelibly employed. The frightful epileptic screams buttressing squalling feedback-laden breakdown, “Totally Natural,” musters perplexingly brain-twisted anguish, funneling Fugazi and Minor Threat’s devious ‘80s-based emotional hardcore desperation through Nirvana’s equally gruesome arsenal raids.

Fans and critics alike hailed the bands’ savage concert performances and were awestruck by Madonna’s primordial creative brilliance. Then, the majors came knocking in the form of Interscope Records. The resulting album, Trail Of Dead’s time-honored Source Tags & Codes, exceeded expectations, bringing further clarity and uniformity to the adrenalized ensemble by intensifying the taciturn pauses with rapturously raucous recoveries. The toxic “Another Morning Stoner” invites comparisons to foremost noise-rock kingpins, Sonic Youth, an obvious Reece influence. The same goes for the buzzing 6-string scrambler bearing the name of decadent French poet, “Boudelaire.” Similarly, atomic powderkeg, “Days Of Being Wild,” plies mangled shrieks to a lashed-out anthem saluting adolescent rage. Audaciously seething manifesto, “Mark David Chapman,” the lone Busch composition, caused outrage since its objectionable namesake cold-bloodedly murdered John Lennon.

Fans and critics alike hailed the bands’ savage concert performances and were awestruck by Madonna’s primordial creative brilliance. Then, the majors came knocking in the form of Interscope Records. The resulting album, Trail Of Dead’s time-honored Source Tags & Codes, exceeded expectations, bringing further clarity and uniformity to the adrenalized ensemble by intensifying the taciturn pauses with rapturously raucous recoveries. The toxic “Another Morning Stoner” invites comparisons to foremost noise-rock kingpins, Sonic Youth, an obvious Reece influence. The same goes for the buzzing 6-string scrambler bearing the name of decadent French poet, “Boudelaire.” Similarly, atomic powderkeg, “Days Of Being Wild,” plies mangled shrieks to a lashed-out anthem saluting adolescent rage. Audaciously seething manifesto, “Mark David Chapman,” the lone Busch composition, caused outrage since its objectionable namesake cold-bloodedly murdered John Lennon.

But times got tough. Continuing to storm the broken barricades of conventionality while heading for a confounded detour betwixt with tribal, Medieval, and tropical wildlife sounds, ‘05s over-intellectualized Worlds Apart came up short as a premature magnum opus. Its ranting title cut cuts too close to neoteric emo as suburban worries concerning BBC, MTV, and celebrity status get snippily bashed. Thankfully, it’s meant as a snippy rip instead of a droll homage. Elsewhere, interconnected drawn-out mantras rule the roost, but some prolonged exoduses barely escape melodramatic mush.

On ‘06s reeling So Divided, the bell tolls for the band on its opening number. Caught in a “Wasted State Of Mind,” they may’ve streamlined overwrought Epicurean grandeur and prosaic Chamber pop dirges at the expense of mystical ceremonial imagery. But there’d be a light at the end of the tunnel as Trail Of Dead left Interscope for well-deserved independence. However, they’ll leave some early fans in the dust and nearly give it all up after getting unfairly chastised on an ill-suited bill supporting faddish Cartoon Network retinue, Dethklok.

These disturbing developments temporarily haunted then halted Trail Of Dead, but better days were just beyond the horizon. Like the proverbial down-and-out artist struggling to maintain footing, Keely gathered his troupes, nourished their collective soul, regained compositional poise, and began fulfilling a real or imagined prophesy. Standing at the precipice of a dazzling resurgence, Trail Of Dead started their own label, Richter Scale Records, and delivered the fully confident ‘09 masterwork, The Century Of Self.

These disturbing developments temporarily haunted then halted Trail Of Dead, but better days were just beyond the horizon. Like the proverbial down-and-out artist struggling to maintain footing, Keely gathered his troupes, nourished their collective soul, regained compositional poise, and began fulfilling a real or imagined prophesy. Standing at the precipice of a dazzling resurgence, Trail Of Dead started their own label, Richter Scale Records, and delivered the fully confident ‘09 masterwork, The Century Of Self.

Religiosity has always been at the heart of Trail Of Dead’s weighty lyrical sensibility. On The Century Of Self, faith takes center stage above social and personal matters. The momentous opening overture, “Giants Causeway,” may appear ominous, but an endearing positivity underscores the remainder. Perhaps seeking a glorified afterlife, the escalating climactic outburst of siren emo-core blazer “Far Pavilions” investigates unclaimed lands that ‘await us beyond the wall of cantonment.’

Though reminiscent of Modest Mouse’s exhilarating seaworthy chants, the sugar-rushed entreaty, “Isis Unveiled,” searches for ‘secrets of the grand design.’ Salvation may fascinate these seasoned warriors, but although they’d be cheerful drafting ‘the song of the ages,’ they just ‘felt like raging’ during sweeping teen-spirited keepsake “Halcyon Days,” revealing a torrential downpour of unfeigned emotionalism. Electrified Pete Townshend riffs infiltrate the core of “Fields Of Coal,” where Keely and Reece wail ‘don’t let him runaway’ with unison impassioned vigor.

The tension mounts from beginning to end for this uninterrupted epic. Feelings of doubt get deliberated upon, especially when the perils of a sustainable musical lifestyle get discussed in song. The suspicious versifying and soared melancholia of “Inland Sea” reluctantly probes the semi-famous lifestyle by inquiring ‘is the price you’ve paid to live this little dream worth the pain you’ve been suffering?’ Pushing aside past insecurities, it’s very likely Keely could now answer affirmatively.

The Century Of Self seems to take on mortality as its central motif.

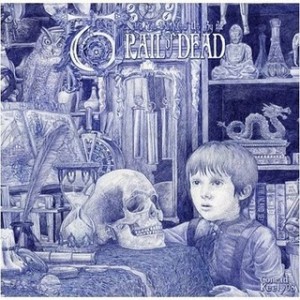

CONRAD KEELY: In the context of childhood perhaps – which I tried to illustrate with the cover artwork. It’s a boy looking at a skull and it’s supposed to represent a moment when a child realizes he’s mortal and will grow up and die. The lyrics, overall, were a reflection of the change we’re undergoing.

Does Trail Of Dead usually extrapolate conceptual themes to enhance each album’s entirety?

Source Tags & Codes explored the dichotomy between hi-tech society and agrarian society. The idea of somebody who moved away from a farm, conceived while touring Chicago, when we went Midwest into the fields, was the inspiration. The next two concentrated on frustration. Worlds Apart railed against our musical environment and peer groups. So Divided reflected frustrations with our label. The big difference with Self is more positive inspiration, starting a new chapter getting away from a major label.

That’s an oversimplification. We use multiple themes and try to make them recur. Theology is close to Jason and I. His family’s Christian. Mine’s completely spiritual, studying Buddhism, Hinduism, and indigenous religions. I can’t help returning to that theme of higher spirituality. “Inland Sea” deals with transcendental meditation, which my parents let me take active part in. “Isis Unveiled” is based on a book I’d see on our bookshelves, flip through, and read. It indicted science and religion. There’s three separate viewpoints from Old Testament God, Lucifer, and finally, Jesus. Each told their story. But it also references unorthodox Christian belief that there were two gods, an Old Testament war-like God who’s overthrown by the peace and love New Testament God.

Who were your early influences?

I got my music sensibility from my parents. I grew up with the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, and Frank Zappa. When my mom got remarried, my stepdad was into prog. He was a drummer. I got into Steve Hillage and Mike Oldfield’s Incantations – a double LP with four sections. Oldfield worked so hard on that record he wore down the 2-inch reel and had to start from scratch. When I was eight, my parents took a trip to England. We lost some money and stayed for two-and-a-half years as a break from Hawaii. That’s when I heard Kate Bush’s “Never Forever.” I had a poster of her in my room that friends would ask about.

In Coventry, where we lived, the whole ska scene happened. Madness were so popular in my school. There was the Specials and English Beat. It was such an interactive lifestyle. Back in America, kids were into Kiss, but didn’t necessarily dress like them. In England, third graders would go to school in trench jackets with The Who stenciled on back. Flight jackets with all those buttons with band names. They took fashion seriously. I got my first pair of Doc Martens at age nine. We looked like thugs. It was hilarious. That was a big musical ingestion. I went back to America and those things weren’t happening yet. Nor would they until my twenties. I never heard Adam & the Ants in America. I got into Classic Rock in high school. But meeting Jason was key. He turned me on to the Replacements, Husker Du, Descendents, Dag Nasty, Cali skate punk. I shifted out of my Pink Floyd-Yes-Genesis mode and embraced it.

Over the course of six albums, including an unheralded self-titled ’98 debut, your lyrics have gotten more deeply romanticized.

Source Tags was very sentimental. There’s songs about the breakup I went through, like “How Near How Far” – the idea of letting go of a muse. There’s no mystery about that. It’s as close as we’ve come to writing a romantic record. The new one’s sentimental, but there’s no love theme. It doesn’t mean we won’t go back to that in the future. Worlds Apart was real political, but not well-timed. Maybe it was three years early. Those things I was pointing my finger at on Worlds Apart were about consumer society, which consumes The Century Of Self. There was a sense that Worlds Apart was informed by the ongoing Gulf War. I tried to address it but the album suffers from being overly ambitious. We were really reaching hard to make a testimonial that’d push our abilities as writers. But we were going through personal stress with Neil leaving the band. That took away from us achieving everything we wanted with that record. I’m proud to have the courage to say those things at the time but I didn’t think anyone wanted to hear them.

Was So Divided a haughtier extension of Worlds Apart?

Except it had no political statement. It didn’t try to reach out to the world. I still think So Divided was a big ‘fuck you’ to everyone. I didn’t want to connect. I wanted to withdraw into our own world and say ‘screw you if you don’t like it.’ I was disappointed with its reception amongst peers and the label. The idea of working on a major label wasn’t working so maybe it was a self-indulgent attempt to get dropped. But The Century Of Self couldn’t have been made if we didn’t do So Divided.The hardest record we ever made was So Divided, especially the painful lyrics. In contrast, The Century Of Self felt easier – the way the songs came together naturally. There were technical challenges with the producer and the studio, but the creative part was unified.

Yet despite So Divided’s muck and mire, there was an unexpectedly upbeat and accessible Carnaby Street-styled Paisley Pop turnabout, “Eight Days Of Hell,” replete with kitsch-y ‘60s multi-harmonies.

I think that would’ve been accessible in the ‘60s or ‘70s. We were basically trying to make our own little Beach Boys song. I had just gotten into Brian Wilson’s Smile record. But it’s more akin to the Hollies “Carrie Ann” or “On A Carousel.” It was fun. The darkness came from its serious lyrics. They’re about a horrible experience opening for Audioslave in the UK. The original lyrics were so dark and mean I was talked into toning them down. Sometimes the whole Shakespeare ‘pen is mightier than the sword’ comes into play. There’s no reason to lash out unreasonably. But it’s fun to get out.

How’d Trail Of Dead get involved with the soundtrack, Hell On Wheels, a documentary about Austin’s new-sprung roller derby scene?

We knew some of those crazy girls. We even performed at one of the roller derby matches. I even sang the national anthem. Austin started the resurrection of roller derby. There was a league that split off and there was a dramatic rivalry.

Speaking of dramatic, have you designed all the eloquent artwork for Trail Of Dead’s album covers?

I’ve done all the design. For the first record, I stole the image from National Geographic. On Worlds Apart, I had someone paint it from a collage I made. So Divided was all done digital. The Century Of Self I did all the art by hand with a ballpoint pen. It took the better part of two years and that’s the stuff I showed at an October ’08 New York exhibition.

Will you remain a transplanted New Yorker for good now?

I loved Austin. One day I’ll go back. There’s an ease to living there. It’s the good life. I was drawn to New York because I felt closer to Europe. I’m still an Irish citizen. I’m not a naturalized American so there’s a yearning to go back to Europe. New York’s supposedly for drunken parties like it’s 1999, but it’s more of a nose-to-the-grindstone-try-to-get-by-and-make-rent city. I’m inspired by everything here. “Halcyon Days” is about making that transition.

At this point, our conversation drifts into the apex of what truly became the premier regenerative thrust of Trail Of Dead’s renaissance. It seems an unwise tour with a Cartoon Network ensemble nearly drove Conrad to quit music before once more getting rejuvenated.

CONRAD: There was this terrible tour we did with Dethklok. They’re an Adult Swim cartoon and the band plays in the shadows, like the Gorillaz. But it’s all about death metal. It’s called Metalocalypse. We were invited to go and all the shows were gonna be free, sponsored by Cartoon Network, and it’d be at all these colleges. Interscope dropped the ball on our college play so we thought it’d be a logical way to hit the market. But it went miserably wrong. All the kids wanted to see was Dethklok. They were awfully hostile audiences. We’d never had that. It was more reminiscent of a London audience when you’re opening for a bigger band like Foo Fighters. Sometimes, when we’d improvise, we’d stop the music just to hear the belligerent audience, then make disgruntled noise. Those were confrontational nights with pissed off fans. But we came out a totally different band. The aggressive battles provided energy and righteous anger. The experience helped unify the band.