FOREWORD: First time I met indie cult fave Mark Eitzel, he was doing a solo acoustic set at CBGB’s 313 Gallery for now-defunct Smug Magazine’s 1st anniversary party. People were talking so loudly it ruined any chance of him being heard above the ruckus. In ’04, his resurrected American Music Club recorded Love Songs For Patriots, one of many career highlights. By ’08, Eitzel’s reassembled AMC clan continued to make evocative pastoral folk on The Golden Age. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Like many young ‘army brats’ living abroad, singer-songwriter Mark Eitzel spent his pre-teen years in faraway Asian spots Okinawa and Taiwan before calling Southampton, England home until age 19. When his father finally got transferred back to Ohio, the post-adolescent Eitzel began playing in Naked Skinnies, a feisty Columbus band inspired by avant-punks the Raincoats and Public Image Ltd. A huge Beatles fan impressed by Elvis Costello’s initial late ‘70s masterworks, he soon moved to San Francisco, forming, then reconstructing praiseworthy underground combo, American Music Club.

Purveying darkly sarcastic humor oft misconstrued as inescapably perplexing melodrama, the ceaselessly cynical troubadour’s early downbeat alcohol-fueled limericks were slapped onto American Music Club’s rushed ’86 debut, The Restless Stranger, and its preferred ’87 follow-up, Engine.

“We were all Anglophiles when we started the band. We did the first record in a hurry because our drummer was going to Germany and we wanted to go there with him to continue as a band. We put out 500 copies in Germany only, then Warner’s later re-released it,” he recalls, citing nascent trepidation. “By Engine, we moved back to America, took the band more seriously, and that album summed up what we do – combining loud distorted guitars with very quiet folk and Country-Western.”

Although American Music Club’s serenely melodious settings suit Eitzels’s disconcertingly deprecating sonnets, the lamenting Frisco transplant concedes to firmly embracing wily Brit-punks as an impressionable youth.

“The first show that blew my mind was the Adverts and the Damned,” Eitzel claims. “But nowadays, if I go out, it’s to a bar, not a club. The trouble is, when someone says a band is the greatest new thing, I’m like, ‘Yeah. OK.’ I’ve heard it before. It kicks ass, but it’s hard for me to get excited about.”

Perhaps Eitzel has trouble enjoying newer talent these days because he has toiled with numerous gifted instrumentalists over the course of several band-related and solo projects. An admirer of considerable pop songwriters such as Neil Young, Elton John, and Joan Armatrading (whose sedate jazzy folk styling embodied Tracy Chapman), the flinty baritone also acknowledges respect for arty prog-rockers Yes and their ilk.

“I listened to Genesis and liked King Crimson’s Red, but I hated ELP, Renaissance, Gentle Giant, and Jethro Tull,” he amends.

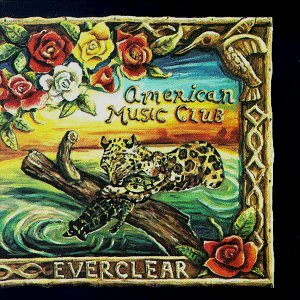

Perchance, these clever artful luminaries could’ve satiated Eitzel’s thirst for intricately moody ambience. An austere rural intimacy dominates ‘88s elaborate California, which runs the gamut from the rousing harmonica-doused honky-tonk “Bad Liquor” to the restrained acoustic somnolence “Last Harbor.” Seldom escaping the barren wasteland of confessional folk-y depressives, ‘91s brilliant Everclear boasted more expansive arrangements, noisier rock moments, and less constraint than past efforts, peaking with the crescendo-filled anthem “Rise” and the speckled “Royal Café.”

Perchance, these clever artful luminaries could’ve satiated Eitzel’s thirst for intricately moody ambience. An austere rural intimacy dominates ‘88s elaborate California, which runs the gamut from the rousing harmonica-doused honky-tonk “Bad Liquor” to the restrained acoustic somnolence “Last Harbor.” Seldom escaping the barren wasteland of confessional folk-y depressives, ‘91s brilliant Everclear boasted more expansive arrangements, noisier rock moments, and less constraint than past efforts, peaking with the crescendo-filled anthem “Rise” and the speckled “Royal Café.”

Better still, ‘93s wide-ranging Mercury fit whirly electronic textures into the mix. Out of its illuminating ashes came the lush piano waltz “Gratitude Walks” and the psychedelic cowpoke roadhouse rant “Crabwalk.” By ‘94s windswept homage, San Francisco, Eitzel broke up American Music Club to start a solo career. Though heartbreak, misery, and vulnerability saturate these endeavors as well, Eitzel appeared upset by concerned fans missing the witty satirical facetiousness his dour lyrics insinuated.

When confronted with the thought that his incipient agonizing shyness may’ve paralleled that of ex-Smiths frontman Morrissey, whose bleak elegies sometimes inform Eitzel’s sulking guise, he gladly proclaims, “Maybe that was true ten years ago. But I think I drank a lot more than Morrissey or I didn’t do the same drugs he did. I love his work, so that’s a compliment.”

Any discomforting reticence and debilitating anxiety seemingly subsided during his ensuing solo quest. ‘96s fine 60 Watt Silver Lining retained the expected inhibited subtlety of yore, but reduced the gloomy insularity and lovelorn despondency for more assured emotional containment. Jazz trumpeter Mark Isham and standup bassist Daniel Pearson offered light Jazz eloquence to Brill Building mementos. Soon after, Eitzel hooked up with Tuatara saxophonist-vibesman Skerik and percussionist Barrett Martin plus pianist-slide guitarist Scott Mc Caughey (Young Fresh Fellows/ Minus 5) and REM guitarist Peter Buck on ‘97s demurely lounge-y West.

“Peter Buck wanted to do a record together,” he explains. “He came to town, we wrote it in three days, and a month later flew up to Seattle. Tuatara was an amazing backup band.”

Taking its protracted title from the hook phrase of Elvis Presley’s heartrending “Suspicious Minds,” ‘98s Caught In A Trap I Can’t Back Out Because I Love You Too Much Baby’s spare tranquility comes closest to the crystalline melancholic flicker tragic ‘70s baroque-folk mystic Nick Drake once wrought. Sonic Youth’s Steve Shelley (drums) and Yo La Tengo’s James McNew (bass) provide poignant rhythm to four songs.

Then came the anguished sadness of ‘01s The Invisible Man, recorded in a living room with acoustic guitar, but later adorned by samplers and MAC G4 computer electronics.

Next, Ethan Johns (of H-Bombs fame) and Joey Waronker (That Dog/ Beck) added surreal backdrop to the mope-y treatments given ‘02s The Music For Courage & Confidence’s borrowed tunes.

In retrospect, Eitzel repents, “That was someone else’s idea. I was persuaded to do a covers-LP to make lots of money. Like a fool, I was left broke. But I love the record even if those aren’t songs I’d normally do.”

However, beautifully brooding pop ballads surveying Eitzel’s American Music Club period were commissioned for ‘03s The Ugly American, which benefited from a full-fledged Greek ensemble. Due to its overseas success, this led him to believe his former mates may want to take another chance in the recording studio. So he re-assembled the still-viable combo, but there was one important difference. Whether intentional or not, his latest songs reflected both the hopefulness and volatility of an unsettled world instead of the dismal sagas of a ravaged individual.

“I don’t know if there’s time left to be a sentimental fad songwriter. Everyone has to be a part of something. The world has changed,” he steadfastly advises.

Eitzel’s spirited maturation shines through the generally upbeat outlook his regenerated American Music Club encourages on ‘04s ambitiously cogent Love Songs For Patriots. The didactic “Ladies And Gentlemen,” whispery sunup resolution “Another Morning,” and fervently uplifting “Only Love Can Set You Free” counter the eerily sorrowful regret “Love Is” and the tangled damsel obfuscation “Job To Do.”

Eitzel’s spirited maturation shines through the generally upbeat outlook his regenerated American Music Club encourages on ‘04s ambitiously cogent Love Songs For Patriots. The didactic “Ladies And Gentlemen,” whispery sunup resolution “Another Morning,” and fervently uplifting “Only Love Can Set You Free” counter the eerily sorrowful regret “Love Is” and the tangled damsel obfuscation “Job To Do.”

On the nearly symphonic stately piano dirge, “Patriot’s Heart,” Eitzel ostensibly addresses the dichotomy of misplaced allegiance, construing vengeance as a positive motivation against evil in a roundabout way.

He shares, “Columbus has the largest gay community in the Midwest beyond Chicago. So I was taking a tour of Columbus gay bars with a friend. There were a bunch of them, many down and dirty. The last one had all these trucks parked outside with American flags. All those guys probably have a wife and kids. Hey, that’s America. Peel back just one layer and you’ve got all kinds of weird shit.”

Though Eitzel tries to veer away from political opinion during conversation, the temptation to express his ideals is too great. Beneath the static guitar fuzz of “America Loves The Minstrel Show” lies a foreboding message listeners should heed.

“Everything that’s in popular culture in America is mediated. America doesn’t accept the real thing, only the cliché of what is real. So that seems how cultures get integrated into America. First you love to hate the cliché, then you hate to hate the cliché. Then, you accept the cliché and the people. But it just doesn’t end. You wish America was smarter than that,” Eitzel avows. “The 2000 national election was the ultimate. Both candidates pose as down home country folk when in fact they’re Harvard/ Yale educated millionaires. Americans love how these guys pretend to be like them when all they’re doing is speaking to the Lowest Common Denominator all the time. People like Bush get voted in out of despair (i.e.: Clinton’s ridiculous ‘I feel your pain’ manifest) People have ideologies but lack common sense.”

Going deeper into governmental contention, he abhors rightwing authoritarian control.

“Any fundamentalist religion is fascism. I don’t think Bush is fascist, but Pat Robertson is. Yet Bush is leaning towards fascist government. If they extend the patriot act, they could arrest you without giving any reasons or access to a lawyer. The arrests at the Republican National Convention – they picked people up who looked like terrorists. They could keep them in jail indefinitely. It’s terrifying.”

Less topically serious, “Myopic Books” finds an unconventional oasis in a snooty bookstore.

“That’s one of those songs the world gives you,” he snickers. “I was in Chicago walking down the street. I’d gotten off the phone with someone filling my ear with how bad their life was and I was like, ‘Fuck you!’ Then, I found a hipster bookstore where they were playing Dinosaur Jr. on the radio and the people were real skinny and unfriendly and I really loved it.”

Still able to conjure the dreary minimalist romanticism Bay Area protégé Mark Kozolek (Red House Painters) took as prototype and the barren stoicism death-obsessed Nick Cave flaunts, Eitzel’s intriguing oeuvre has now expanded beyond confining morose boundaries. He now counteracts dry innuendo with moist directness, exhibiting innermost feelings of glee, contentment, and hesitancy while circumventing the profound neuroticism afflicting earlier musings. Love Songs For Patriots reaffirms Eitzel’s (and thus, American Music Club’s) sordid sense of humor about misery while fondly propagating nationalistic pride and rejuvenating adoration for wizened mortals.