OK. The headline is an old joke concerning a pastor’s member going ‘past her fur,’ if you get my meaning, if you catch my drift. All kidding aside, Blitzen Trapper’s psych-folk sound embodies a modicum of religiosity. After all, leader Eric Earley met fellow guitarist Marty Marquis at Covenant College, a Presbyterian school in Georgia. Plus, Marquis admits his father, an actor, listened to church music as well as AM Top 40 and show tunes. Besides, it may be a stretch, but the eerie “God + Suicide” seems to hit upon misbegotten spirituality.

OK. The headline is an old joke concerning a pastor’s member going ‘past her fur,’ if you get my meaning, if you catch my drift. All kidding aside, Blitzen Trapper’s psych-folk sound embodies a modicum of religiosity. After all, leader Eric Earley met fellow guitarist Marty Marquis at Covenant College, a Presbyterian school in Georgia. Plus, Marquis admits his father, an actor, listened to church music as well as AM Top 40 and show tunes. Besides, it may be a stretch, but the eerie “God + Suicide” seems to hit upon misbegotten spirituality.

“That’s a subject that’s important for all-time, like love, death, and nature,” Earley confides.

Marquis concedes, “Faith has a broad influence in American society. Kids brought up in the church get imprinted with that. On our records, Eric makes it his own. But I don’t think he used any institutional alliance. It’s just one person’s way of understanding America’s religious heritage.”

It’s true. A certain pietistic solemnity slips into various secular tunes on Blitzen Trapper’s kaleidoscopic fourth album, Furr (Sub Pop). Though taking more inspiration from elder statesman, Bob Dylan, and the timeless folk tradition, this countrified Portland quintet take that acoustic heritage in unexpected directions without losing topical focus or abandoning general indoctrinated themes.

It’s true. A certain pietistic solemnity slips into various secular tunes on Blitzen Trapper’s kaleidoscopic fourth album, Furr (Sub Pop). Though taking more inspiration from elder statesman, Bob Dylan, and the timeless folk tradition, this countrified Portland quintet take that acoustic heritage in unexpected directions without losing topical focus or abandoning general indoctrinated themes.

Many specific reference points get blurred moving beyond mere archival reverence, but Blitzen Trapper surely wear their influential vestiges well. Whereas the teenaged Marquis worshipped the Beatles, an apparent source for his troupe’s musical leanings, Earley discovered John Denver, Crosby Stills Nash & Young, and bluegrass through his father. Constructing sweetly artful indie pop from a stripped-down rural Americana foundation stretching back to the Great Depression may’ve been less effectual had these reluctant hipsters, except Marquis, not grown up in the formerly agrarian confines of Salem, Oregon.

“We’re Salem natives,” Earley concurs. “It was like any other American po-dunk place. Growing up, there were farms, now there’s strip malls, Wal-Mart, and no city center. We got out as fast as we could.”

On Furr, these congenial northwestern pals put their best foot forward on infectious soul-drenched mini-opus, “Sleepytime In The Western World,” grafting The Band’s “Up On Cripple Creek” organ motif to mid-period Beatles guitar fills and tremolo bass, coming up with a cacophonous glam-affected “Eight Miles High” swirl perfect for sunset.

“That’s actually a song within a song. It drops down into a dreamy story,” grants Earley.

Nearly as complex and just as hooky, “Gold For Bread” takes broken-down suburban Blues on an upward pre-choral electro-guitar ride.

Earley laughs, then states, “Everybody describes my stuff differently. At this point in rock, the Beatles and Byrds are so ingrained those come out without us thinking about it. If you worked at a pizza parlor or corner store, that was on the radio or at dances. It’s easy for us to mix that in with all the new directions in musical progression. Beck’s early records blended folk with hip-hop and soul. I think you have to be literate in the history of rock if you want to make something true nowadays. If not, it may lack substance or familiarity.”

Easy flowing title track, “Furr,” perhaps an appellation combining a bear’s burr with its craved prey’s fur, serves as an adolescents’ campfire retreat that’d fit alongside Conor Oberst and Iron & Wine’s best soliloquized mementos. Then again, Earley’s high-pitched harmonica dupes Dylan and moreover, his breezily understated vocal detachment and murky self-examination recalls shy heroin-addled suicide victim, Elliott Smith.

Earley doesn’t disagree with this blown-up assessment, yet disputes claims concerning post-grunge neo-folk luminary Smith’s self-inflicted stab wounds. “Did he kill himself? That’s questionable.”

What’s not disputable is the literary sway Earley’s songwriting, and taciturnly, contemporary Portland peers such as Stephen Malkmus, the Decemberists, and Modest Mouse, luminously reflects. Western sci-fi and respected American authors such as Steinbeck, Faulkner, and Mc Carthy occupy a special place in his heart.

Earley quips, “It rains a lot in Portland. We’ve got tons of time to read – with few distractions. But most people emigrate here.”

Setting up shop at the turn of the 21st century, Blitzen Trapper, filled out by tight brethren Erik Menteer (Moog-guitar), Drew Laughery (keys), Michael Van Pelt (bass), and Brian Koch (drums), create what’s been described as an ‘eccentric mosaic’ of country waltzes, folk ballads, and freaky experiments. They record in an old Willamette River building at Sally Mack’s School of Dance, using an ad hoc studio and cheap gear. Weighing heavy on their choice of space are elements of comfort and informality.

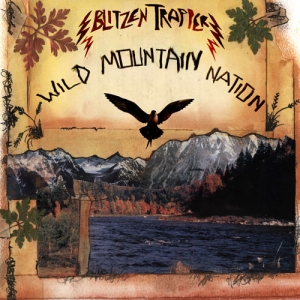

“Our first self-titled album was a compilation of music that came before. It’s not that cohesive and the music’s not that good. There are a few songs I really like, though,” Earley explains. “The second one, Field Rexx, is like the beginning of lo-fi folk rock while Wild Mountain Nation is the culmination and did real good. Furr is more hi-fi and consistent as far as the sound goes, but probably not the style of the songs. People think it jumps around quite a bit. But it’s all-American music at heart.”

“Our first self-titled album was a compilation of music that came before. It’s not that cohesive and the music’s not that good. There are a few songs I really like, though,” Earley explains. “The second one, Field Rexx, is like the beginning of lo-fi folk rock while Wild Mountain Nation is the culmination and did real good. Furr is more hi-fi and consistent as far as the sound goes, but probably not the style of the songs. People think it jumps around quite a bit. But it’s all-American music at heart.”

Wild Mountain Nation gave ‘em a radically ambitious breakthrough. “Devils A Go-Go” mingles complicated Beefheart spasms, choppy deconstructed rhythms, and fracturing guitar splinters onward towards its sunny climactic vista. Contrasting this somewhat unconventional opener is the title track’s country bumpkin rural escapism and the melodic piano appeasement, “Futures & Folly.”

But ultimately, as the distortion-pedaled static-doused rummage “Miss Spiritual Tramp” proves, the decision to stay ‘wild’ inside this ‘mountain nation’ outdoes any notion of tangible roots-based connectivity. Offering further evidence, the euphonious bleating sound waves usurping “Sci-Fi Kid” suggests a zany Zappa zestfulness. On the other hand, dulcet flute and earthy harmonica ensure pastoral retrenchment, “Summer Town,” while honeyed steel licks and an acoustic fireside chorus saddle “Country Caravan.” It’s when they go straight down the middle and try their hand at power pop that the results benefit both countrified minions and hardened experimentalists alike. At least that’s the case with “The Green King Sings,” a fairly perplexing dual axe hoedown loosely reminiscent of underground ‘70s legends Big Star until its molten meltdown.

It’s this apparent yin and yang approach that unfailingly consumes Blitzen Trapper. Don’t put any pigeonholed tags on them or suffer the consequences. Musically advanced, conscientiously aware, and loaded with boundless apparitions, the defiant sextet are absolutely unapologetic in respect to the tangled webs they weave.

Earley concludes, “I hate doing the same thing twice.”