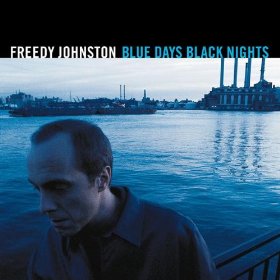

FOREWORD: In the late ‘90s, I got to meet Freedy Johnston several times at small clubs in Manhattan. He was almost a fixture, attending shows when he wasn’t doing gigs at Brownies on Avenue A or Mercury Lounge at nearby Houston Street. But after this interview promoting ‘99s Blue Days, Black Nights, he has kept a rather low profile. ‘01 Right Between The Promises went unnoticed and ’07s covers album, My Favorite Waste Of Time, barely made a sound, except at Fordham’s WFUV, where I heard the Marshall Crenshaw-written title track once. Happily, ‘99s Rain On The City gave Freedy a rebirth of sorts. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Talented singer-songwriters Elliott Smith, Ron Sexsmith, Will Oldham, Bill Callahan, Lou Barlow, and Mike ‘Sport’ Murphy could be considered ‘sensitive ‘90s males.’ Generally taking an acoustic storyteller approach similar to ’60 folk-pop progenitors Tim Hardin and Leonard Cohen, they convey conflicting emotions, revealing painful romantic disappointment alongside the intimate hopefulness which lies just beyond the gray skies.

Likewise, one of he most melodic, reflective, and abstract of these soul-bearing bards happens to be Kansas-raised New York-based Freedy Johnston. By working his aching, majestic, ascending tenor through bleak, fleshed-out arrangements, Johnston’s somber soundscapes capture the quiet resolve and private intimacy of an experienced troubadour.

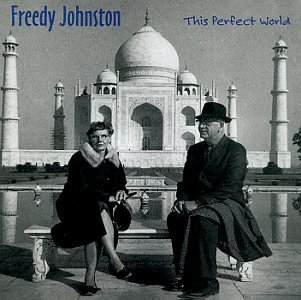

Since ‘90s plaintive The Trouble Tree, Johnston has released the markedly improved Can You Fly, the sarcastically titled gem, This Perfect World, and the nearly lost-in-the-shuffle Never home.

With the help of seasoned producer (and acclaimed recording artist0 T-Bone Burnett, Blue Days, Black Nights may be his most fully realized work yet.

With the help of seasoned producer (and acclaimed recording artist0 T-Bone Burnett, Blue Days, Black Nights may be his most fully realized work yet.

The alluring melodicism of the balmy “Underwater Life,” the summery effervescence of “Change Your Mind,” and the delicate flow of “Until The Sun Comes Back Again” contrast beautifully with the introspective downhearted lament, “The Farthest Lights,” and the sad, slow moving “Emily.” All told, Blue Days, Black Nights cements Johnston’s reputation as a genuine, well-focused pop craftsman.

Who were some of your early influences?

FREEDY: I don’t put myself in the company of Elvis Costello and Neil Young, but I’d cite them as people whose shoulders I stand on. Neil Young’s an archetypal singer-songwriter who invented a cool melding of Country to rock in a very unpretentious way.

Although you’ve lived in New York City for many years, your songs seem to have a rural flavor.

FREEDY: Each record for me is a project. Some of the songs tend to have familiar themes, but This Perfect World’s images were about New York City. Can You Fly may have rural images, but I don’t know if you could find any rural influences on the new record. The opening song is set at sea and the others are set in city streets, although I don’t give much detail as to what time or place the songs were in, Each song has its own vocabulary and rules. Some lines are out in leftfield on the new record because I had this constant battle in my mind between making sense and trying to give a pleasing sound to the line – which often means not making sense and balancing the two. Often, I have to go with my own interpretations of words. Some people write from diaries. I don’t. I make melancholy songs that don’t reflect my life.

FREEDY: Each record for me is a project. Some of the songs tend to have familiar themes, but This Perfect World’s images were about New York City. Can You Fly may have rural images, but I don’t know if you could find any rural influences on the new record. The opening song is set at sea and the others are set in city streets, although I don’t give much detail as to what time or place the songs were in, Each song has its own vocabulary and rules. Some lines are out in leftfield on the new record because I had this constant battle in my mind between making sense and trying to give a pleasing sound to the line – which often means not making sense and balancing the two. Often, I have to go with my own interpretations of words. Some people write from diaries. I don’t. I make melancholy songs that don’t reflect my life.

What affect did producer T-Bone Burnett have on Blue Days, Black Nights?

FREEDY: T-Bone helped me sharpen the lyrics and shape them down. A point in our conversation was how much sense should I make without giving away a song’s mystery. If a line sounds beautiful and sets off mind associations’ leave it. That’s hard for me to do. I consider myself closer to a furniture maker or craftsman sometimes. T-Bone is such a mature, spiritual guy. Like most older artists, he gives the same advice: listen to your gut and trust yourself. He comes from a looser, almost painter-like attitude of ‘throw it up and see what it looks like. His impetus on trying to get a live performance sound in the studio really made the album happen. I wanted to get a live vocal on these songs, like Frank Sinatra. I was a big Sinatra fan. So T-Bone said, ‘let’s try it.’ We set up the studio with the mike right in the middle of the room. Several takes resulted in original vocals being used. There’s something you can’t create when you overdub a vocal. And we tried to pull it off as best as we could.

So you didn’t over-rehearse the songs, because they may have come out too stiff.

FREEDY: Maybe. What happens in the studio is, I get a little conservative and too critical. So, the first two takes will often have mistakes I’d pass over. While working on this record, T-Bone would say, ‘listen to how we really swung on the first take, even though the band didn’t know the song so well. It really had a life to it.’ I was often wrong and my opinion overruled. But I learned a lot about the real value of the freshness found on a first take. I’ve heard Elvis Costello talking about it with a record he did with T-Bone called King Of America. They did most of it live, and the musicians didn’t know the songs beforehand. That’s like how Bob Dylan worked for a long time. I’m amazed how loose and sloppy you could be in the studio. But by the end of the mix, the songs sound great. In a nutshell, I’m less afraid of mistakes.

Your albums seem very uniform in approach. How does each differ?

FREEDY: As far as uniformity, I can’t escape that. It’s best to stick to your strength. I remember Pete Townshend saying all songwriters compose two or three songs over and over again. His songs are all over the map and his personality comes out. So my goal is to develop compositional ability. My song structures won’t get more complex. But that subtle marriage between melody and lyric, who knows how it works? I try to get better at it. It’s difficult writing lyrics and matching them to melodies. But I’m happy with the sense the new songs make, even though they’re not simple-minded lyrically. It’s the Midwestern mindset of trying your best. I hope I don’t have too many boring cliches. I’m not gonna do hip-hop, swing, or a Sugar Ray reggae-pop song. I take my records very seriously. I grew up in the ‘70s. So I believe albums are where the songs live forever. I can’t imagine hearing Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti and David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust any other way. Each record has its own signature sound.