It’s lamentable how often death provides meaningful stimulus for musicians of all stripes. Sometimes it redeems otherwise reluctant artists to dig deeper for that extra motivational spark that puts them over the top. Yet it’s a sad predicament understood all too well by New York-based acid house enthusiasts, Gang Gang Dance.

It’s lamentable how often death provides meaningful stimulus for musicians of all stripes. Sometimes it redeems otherwise reluctant artists to dig deeper for that extra motivational spark that puts them over the top. Yet it’s a sad predicament understood all too well by New York-based acid house enthusiasts, Gang Gang Dance.

An early Gang Gang Dance comrade, Nathan Maddox, was struck to death by lightning on a Chinatown rooftop in ’02. Since then, the posthumous teen has provided inspirational guidance from beyond the grave. Post-haste, the surviving members became far more effective transferring their picturesque embryonic concepts into transcendent ‘theatre of the mind’ abstractions. A challenging self-titled ’04 album appeared and the band improved so quickly they were eventually spotted supporting clever underground heavyweights Sonic Youth, Massive Attack, and TV On The Radio.

Vigilant Gang Gang Dance front man Brian Degraw shirks at any high-brow notion of sophisticated shrewdness and insists, “It’s not a super-intense intellectual process we’re unloading.”

A promising Washington DC art school student, Degraw had developed a liking for local post-punk renegades Fugazi and Nation Of Ulysses, then met Michigan native Tim Dewit, another creative alchemist struck by the deep emotional intrigue consuming both visual and audio arts.

Upon moving to New York City, the percussive duo soon hooked up with guitarist Josh Diamond and eccentric vocalist, Lizzi Bougatsos, using borrowed instruments, looped samples, and impromptu jams to design constantly evolving musical templates at a practice space shared by innovative peers, Black Dice and Animal Collective. As they got proficient melding spontaneous musical sequences into minimalist orchestral constructions, the experimental foursome precipitously gained a foothold as subterraneous vanguard luminaries.

Following ‘05s relatively conventional God’s Money, Degraw’s crew spent a good portion of the next year constructing the chillingly variegated 3-song 20-minute EP, Rawwar. Here, they tossed Middle Eastern elements into fantastical bombastic dreamscape “Nicoman,” reveled in synthesized Industrial-strength electronica on dramatic cloudburst “Oxygen Demo Riddim, and submerged fluttery electrodes beneath the paradoxical mind-boggling liturgy “The Earthquake That Frees Prisoners.” But this was just a deserving primer for the Gang.

With Retina Riddim, a spare 24-minute instrumental, Degraw combined his abstruse musical objectives with potent cinematic ambitions, creating a mesmerizing half-hour DVD as a ceremonial adaptation. An air of brooding mystery and unsettled anxiety camouflage this apprehensive art-damaged requiem. Sound-wise, glacial violins intertwine with dreamily ambient oscillations, abrupt sine waves, and faux-orchestral bits, detonating into a choppy rhythmic deluge.

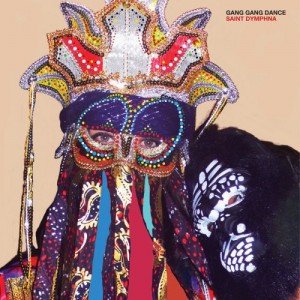

An increasing amount of humbled admirers eagerly awaited Gang Gang Dance’s next endeavor, especially since each preceding release had subsequently advanced their compact legacy fashioning mutated modernistic mosaics. Named after the patron saint of sufferers, ‘09s urbane portraiture Saint Dymphna (Warp Records) opens up and brightens the dynamic scope of Gang Gang Dance’s pan-cultural adventuring. A crisper, livelier production sheen enhances thoroughly efficient stylistic ideas. It’s undeniably a significant step up for Chinatown transplant, Degraw, and his impressive crewmates. No doubt Lower Manhattan’s diverse multiethnic art scene again enlightened him in a forthright manner. As always, Degraw’s striking cover artwork helps visualize the painstakingly perfected project.

An increasing amount of humbled admirers eagerly awaited Gang Gang Dance’s next endeavor, especially since each preceding release had subsequently advanced their compact legacy fashioning mutated modernistic mosaics. Named after the patron saint of sufferers, ‘09s urbane portraiture Saint Dymphna (Warp Records) opens up and brightens the dynamic scope of Gang Gang Dance’s pan-cultural adventuring. A crisper, livelier production sheen enhances thoroughly efficient stylistic ideas. It’s undeniably a significant step up for Chinatown transplant, Degraw, and his impressive crewmates. No doubt Lower Manhattan’s diverse multiethnic art scene again enlightened him in a forthright manner. As always, Degraw’s striking cover artwork helps visualize the painstakingly perfected project.

Computer generated bleats and burbles get inside the exotic jungle groove of tribal sub-Saharan opening jolt, “Bebey.” Ensuing syncopated Afro-funk shuffle, “First Communion,” a click track reminiscent of goodly Malian duo Amadou & Mariam, showcases Lizzi’s arousing goth caterwaul, which rises out of the abyss with a brayed trill, upending the linear percussive stomp and overblown bass contortions. Though its sympathetic instrumental preponderance and No Wave electronic squiggles lack an enigmatic African influence, the neo-Classical faux-string ethereality of “Blue Nile” does apply distantly sequestered primordial voices to mirror its titular meandering river.

Lizzi takes complete control on arrhythmic wasteland distention, “Desert Storm,” attaining majestic operatic heights merging Bjork’s diva-esque hysterics, Lene Lovich’s hiccuped gulps, and Poly Styrene’s adolescent rage. On accessibly posh mantra, “House Jam,” her childlike quaver reaches its stratospheric zenith, recalling Kate Bush’s monastic rendering of “Running Up That Hill” a tad.

Onward, an extraterrestrial motif underscores the balance of Saint Dymphna’s surrealistic ensemble. Interplanetary sounds beam in and out of “Princes,” a showcase for unrenowned Brit rapper Tinchy Stryder, whose urban flow grounds the aerobic electro-dance pulse and credibly filches the conversationalist routine of better-known countryman, Mike Skinner (a.k.a. the Streets). Further otherworldly collations abound when laser beams zoom across muted percussion during “Inners Pace,” where tubular sound effects fade out then reestablish the jittery horn-punctuated scheme.

Degraw truly opens up during conversation when examining his deceased friends’ extemporaneous narrative woven through Rawwar’s “The Earthquake That Frees Prisoners.”

“The closest we come to having a theme is Nathan. He was a close friend who joined up when he was sixteen in DC. Basically, he was the most mystical, otherworldly person I’d ever met. Since he left, everyone has been living better, so he fills the role of a shaman. He brings a strong spiritual aspect to the band – his energy, personality. The way he lived life was inspiring.”

How does your visual arts background positively affect Gang Gang Dance’s music?

BRIAN DEGRAW: It’s a big influence on our music, almost more so than music, but in a strange way. It’s something that’s relative, ‘visual music,’ seeing it as well as hearing it – the shapes and the colors.

When did you become involved with the club scene?

When I was sixteen, I moved to DC. That’s when I got more influenced by that culture. I’d attended raves, but never really liked it. When I started hearing London grime, house, and garage music, that was my first positive exposure to club music around 2003. That’s when I started investigating that realm.

GGD’s studio tracks seem deliberately structured, yet freeform in approach. Do your songs usually come from improvisational jams?

Almost always they do. That’s how we started. We didn’t write any structured pieces. Now we compose structured pieces but it all stems from improvisation. We don’t go into the studio with parts and ideas. We just play for hours, listen back, find a spot we like, and continue building upon that.

Were you encouraged in any way by obtuse ‘80s experimentalists such as Psychic TV, Throbbing Gristle, or Einsterzende Neubauten?

Yeah, for sure. At one point in my life, that was exciting, but I don’t get to listen to that stuff anymore. However, their approach affected my direction.

Were Rawwar and God’s Money semi-conceptually designed?

It’s all about exploration. We get bored easily and won’t be happy doing something over and over. We listen to so much different music we’re interested in and get influenced by that. We hate stagnation. The shows we’ve been playing lately don’t feature songs from the new record. We’ve already written new stuff and got bored with the new album.

How has Gang Gang Dance grown or evolved since its inception?

I’m not sure how it happened. There’s no line to be drawn. No matter how much time I take looking back at each record, I can’t figure out how or why. (laughter) It’s more on instinct than any conscious methodology.

“Bebay” and “First Communion” both utilize tribal African beats. Are these newer influences showing up firsthand?

Those are things we’ve listened to for a long time but we’re very gradual in compositional approach. We don’t rush anything. We basically start out making noise music – banging on things trying to emote something. When that felt redundant, we considered structure more. But God’s Money was the first time we did that. Again, it wasn’t conscious. It was done out of frustration and boredom. Improvising became limiting in a way so we started having repetitive parts. From there, it’s been a hodgepodge of all these elements. It’s about being ‘in the moment’ and capturing it on tape. I think there’s a theme for Saint Dymphna, but I don’t know what it is. It’s more on a spiritual level than anything we can describe as progressive.

Where’d you find rapper, Tinchy Stryder, whose flow saddles “Princes”?

When I first heard grime music, a friend from London gave me a cassette of pirated recordings. It was hours long. These MC’s did their thing over tracks. It’s more mainstream now but at the time there was a very good underground movement. When I first heard the tapes, I was completely blown away by the eastern melodies, rawness of the beats, and off-ness of timing. One of the first MC’s I heard was Tingy. I was an instant fan. He was only fifteen at the time. He blew my mind. It was alien music to me. We toured London, a kid found out we were a fan, and tracked him down. He freestyled over some beats and then we refined it into a more finished song.

Have you ever contemplated doing cinematic scores?

Yeah. We’d love to. That would be perfect. So much of what we do is based on feeling. It would be very appropriate. Tap into the film’s emotion and put it into shape.