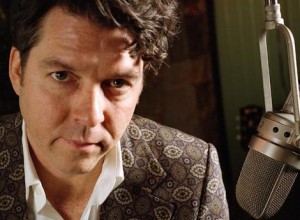

FOREWORD: I remember Joe Henry getting his new silk shirt burnt by the ashes from an incense stick at Southpaw in Brooklyn during my interview. He was not amused but at least thanked me for letting him know I saw it happening. Anyway, Henry’s been on the cusp of fame for years. He married Melanie Ciccone, Madonna’s sister, who thankfully convinced the enduring bard to give the pop superstar, “Don’t Tell Me,” for inclusion on her fabulous Music LP. I bet that song’s made Henry more money than his entire output. ‘07s excellent Civilians was followed up by ‘09s passionately mesmerizing Blood From Stars. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

FOREWORD: I remember Joe Henry getting his new silk shirt burnt by the ashes from an incense stick at Southpaw in Brooklyn during my interview. He was not amused but at least thanked me for letting him know I saw it happening. Anyway, Henry’s been on the cusp of fame for years. He married Melanie Ciccone, Madonna’s sister, who thankfully convinced the enduring bard to give the pop superstar, “Don’t Tell Me,” for inclusion on her fabulous Music LP. I bet that song’s made Henry more money than his entire output. ‘07s excellent Civilians was followed up by ‘09s passionately mesmerizing Blood From Stars. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

As singer-songwriter Joe Henry stands at the foot of Brooklyn’s Southpaw stage, guitar slung to the side before performing another fresh Tiny Voices track, he calmly quips, “I thought this song (the urbane “Flag”) was too political, but my wife said, ‘Your songs are so obtuse, no one will notice.’” The mostly seated audience politely chuckles, then afterwards give the seasoned rhapsodist resounding applause, beckoning him for a merited encore following a perfectly poignant stream of distended hymnal odes flaunting sundry emotional angles.

Though neither overtly political nor outlandishly askew, Henry’s expansive oeuvre does reveal an oblique Bob Dylan influence. At age eleven, his older brother traded a Steppenwolf album for Highway 61 Revisited. It was a galvanizing moment that spoke to him instantly. A fearlessly creative troubadour residing in Los Angeles since ’90, Henry found initial acceptance while living in New York City when his earliest demos were pressed to vinyl as Talk Of Heaven by Profile Records (a local label branching beyond rappers Run DMC).

“I’d always been infatuated with music. I grew up in the South listening to Dusty Springfield, Ray Charles, Johnny Cash, and Buck Owens. At seven, I obsessed over Glen Campbell doing Jimmy Webb songs. “Galveston” was the first 45 I purchased,” the eager maestro shares. “My parents had a great appreciation for authentic Country, but they never went out to find it. They were incredibly hard working – not people of leisure. The only three records they had were Dionne Warwick’s Greatest Hits, Delaney & Bonnie’s Motel Shots – a fantastic record, and an Andy Williams’ Christmas record.”

Signed to A & M Records, Henry’s next step was to record ‘89s promising Murder of Crows. Initially conceived as producer Anton Fier’s latest Golden Palomino project, featuring ex-Rolling Stones guitarist Mick Taylor and Allman Brothers keyboardist Chuck Leavell, the set hearkened to ‘70s classic rock radio. ‘90s ensued Shuffletown pared down Henry’s acoustic moodiness for finely wrought blue-eyed soul. Firmly in charge and acutely aware of the intricacies involved with compositional construction, his tuneful signature could be felt firsthand.

“When you’re young, you think of songs as potatoes coming out of the ground fully formed, thus the idea where someone is treating a song, producing it, and giving it a sonic perception becomes reality later,” declares Henry.

Hooking up with prestigious alternative Country band, the Jayhawks, the re-stimulated Henry’s melancholic hopefulness invigorated ‘92s widespread breakthrough Short Man’s Room and its battle-scarred follow-up, Kindness Of The World. Through a hazy ominous daze, his intimately reedy baritone rasp poured out wounded sentimentality, intuitively forecasting ‘all news will be good news from now on’ during the deeply felt pedal steel-mandolin-fortified “Fireman’s Wedding.”

About the prophetic merger, Henry recollects, “I had lost my A & M deal and the Jayhawks were between labels. It was a marriage of convenience. They lived in Minneapolis where there was a serious, disparate music community including the Replacements, Soul Asylum, and Twin Tone bands they felt part of. They approached music as a band, but I was touring for Shuffletown, which featured Jazz artists Don Cherry and Cecil Mc Bee. I found it hard for the Jayhawks to play those songs. They didn’t fall into their bag very easily. The songs were claustrophobic onstage while their thing was loose and open. So I tried to do something that was authentic to them and wrote Short Man’s Room as an idea of working within a bands’ mindset.”

Recruiting Page Hamilton of metallurgists Helmet for ‘96s broad abstraction Trampoline furnished Henry’s drifting lovelorn dirges with tremolo-ensconced dissonance and symphonic drones.

Henry admits, “We were both Miles Davis freaks. Helmet had opened for Henry Rollins at L.A.’s Olympic Theatre and he had great midtempo and slow grooves reminiscent of Miles’ electric period. I thought to invite him onboard would give me a whole new perception and he responded in a way that was authentic to him.”

By ‘99s loop and sample-aided Fuse, he convened with respected producer Daniel Lanois to appease a growing fan base heeding every whim.

“The songs wouldn’t arrive as they have if I was thinking in a fully Country lexicon. If those were the only colors in my palette I couldn’t write the way I do now because there’s no context for them,” he observes.

So despite retaining his contemplative maudlin tone on distant abstruse dreamscapes, Henry moved forward once again for ‘01s eloquent Scar, enlisting Jazz icon Ornette Coleman to blow free form sax above the wearily morose opening profile “Richard Pryor Addresses A Tearful Nation” and an unlisted bookend solo excursion. Aiming past the boundless confines of modern folk flirtation with help from ‘jazzbos’ Brad Mehldau and Marc Ribot, Scar gained critical plaudits but confused eager minions readied for acoustic retreat.

So despite retaining his contemplative maudlin tone on distant abstruse dreamscapes, Henry moved forward once again for ‘01s eloquent Scar, enlisting Jazz icon Ornette Coleman to blow free form sax above the wearily morose opening profile “Richard Pryor Addresses A Tearful Nation” and an unlisted bookend solo excursion. Aiming past the boundless confines of modern folk flirtation with help from ‘jazzbos’ Brad Mehldau and Marc Ribot, Scar gained critical plaudits but confused eager minions readied for acoustic retreat.

Henry ascertains, “It’s been many years since I’ve played anything pre-Trampoline onstage. Those songs don’t lend themselves to the interpretation I’m interested in now, which is why my writing style has shifted some. I’m looking to write songs that are more open with fewer chord changes, not constricting musicians. My records may not be connected in a linear way, but the thematic point of view should come through like a movie.”

Still enamored by the vast breadth of improvisational spontaneity, Henry signed to burgeoning indie Anti Records, securing esteemed clarinetist Don Byron and limber trumpeter Ron Miles for ‘03s deviously genteel Tiny Voices. His compellingly dreary lamentations desolately flutter in the wind with David Palmer’s languid piano ripples and overcast orchestral compensation richly adorning understated metaphoric ambiguity. An atmospheric lull befalls the transcending title cut, the crestfallen “Sold,” and the somber “Animal Skin.” A murky midnight gloom worthy of Tom Waits affects “This Afternoon,” a temperate soulful saunter that’d fit comfortably alongside lowdown alt-rock drones Lambchop, Tindersticks, and Nick Cave. Henry’s most dramatically elliptical utterances complement the relaxed groove.

Concerning his keen lyrical propensity, Henry insists, “Lyrics have never been a sidebar. I’ve always taken them very seriously and I’m a savage self-editor. I enjoy that stage of writing when a song has identified its character enough so you could step away. It’s not gonna evaporate, but it’s still viscous and pliable.”

As for the Jazz-informed meditations consuming Tiny Voices, he surmises, “I have a great love for Jazz, but I’m not trying to make Jazz music. I’m trying to incorporate certain Jazz tonalities because I appreciate those colors and that approach to freedom. When rock started, Little Richard made records when this was a maverick industry. It wasn’t so cut and dry. Look at The Clash, they improvised within the structure of a song until it gelled. That’s how Jazz players used to work, though they frequently don’t anymore.”

Besides his own work, Henry produced Soul legend Solomon Burke’s triumphant ‘02 comeback Don’t Give Up On Me and wrote his famous sister-in-law Madonna’s hit single “Don’t Tell Me.”

“I wanted Solomon to be a bandleader with his big voice,” he says of Burke. “Initially, he was spooked by how exposed his vocal was. He was used to chicken scratch R & B guitar, not acoustic guitar – which had a different function. I stuck to my guns and kept it immediate and raw.”

But his most lucrative payday came when pop diva Madonna struck gold with Henry’s “Don’t Tell Me.”

He concedes, “It was written quickly and dashed off in a half-hour. I listen to tons of Sinatra so I was working it in a Classic standard way. She responded to it instantly. I certainly didn’t think it would be a single. I thought it was trivial.”

As for future endeavors, Henry shockingly concludes, “I’d like to work with (hip-hop trailblazer) Dr. Dre. I think he’s bad ass. I’d be curious to see what he’d do with someone like me.”