FOREWORD: For a couple weeks there in the summer of ’05, I became friendly with mod folk rascal, Langhorne Slim. I caught a few shows (one with my college bud, Jeff), quaffed a few brews, and took some quotes on the run. His self-titled ’08 album is nearly as good as ’05 long-play debut, When the Sun’s Come Down. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Tackling interpretive folk and talkin’ blues in a dignified roots-y rock manner, young buck Langhorne Slim proves a simple song goes a long way. Taking his adopted first name from the rural Pennsylvania town he departed following high school, the sprightly Slim (a.k.a. Sean Scolnick) feels perfectly at home composing scanty hobo lullaby’s, convivial old timey treatises, and assiduously finger picked hillbilly hoe-downs.

Drawing a passing resemblance to soulful Philly peer Amos Lee, the adroit Slim delivers post-adolescent confessionals in a slightly nasal tone prudently located to the right of strangely scraggly baritone grumbler Tom Waits and wild West Virginian warbling weirdo Hasil Adkins.Leaving the agrarian farmlands of Bucks County to attend SUNY-Purchase in Westchester, Slim then moved to Jersey City and Brooklyn before settling in New York’s Chinatown district with his girlfriend.

Brought up by his mother and grandparents, he discovered theatrical soundtracks, Jazz, and Barbra Striesand as a child. On Sundays, his divorced father would visit, exposing him to Chuck Berry and the Rolling Stones.

“I’ve seen Richie Havens live more than any other performer. Last time I saw him, he played a haunted Pennsylvania hotel. His hands are enormous. Because he didn’t break any strings banging away I asked what kind he used. He said, ‘D’Addario,’ so I’ve used them ever since. But I break them all the time. In fact, when Havens was at Woodstock, he broke a bunch during “Freedom.” He plays in such a rhythmic way,” Slim instructs. “As for Doc Watson, he’s maybe my favorite guitarist. I find comparisons to him to be huge compliments. Tonight, someone said early Dylan. However, that’s probably only because he played acoustic guitar and took inspiration from the same American folk roots music.”

“My grandfather taught me about Lionel Hampton and I was doing community theatre – Guys & Dolls and famous ancient plays – but I was never any good at being directed, so I decided to make my own kind of show,” Slim shares. “At thirteen, I picked up a guitar and began writing.”

After college, Slim made minimalist self-released home recording, Slim Picken’s, with friend Charles Butler on banjo. Soon, indie label Narnack signed him for the introductory Electric Love Letter EP, a less laid-back, more festive, yet hastily assembled project that gained the attention of neo-traditionalists and anti-folk contemporaries alike. Slim’s eyes light up when compared to interpretive post-Dylan strummer Richie Havens and bluegrass icon Doc Watson.

Onstage at quaint NoHo Manhattan club, Joe’s Pub, his unwavering confidence, facetious wit, and quickly quipped asides kept the seated audience captive. Allowing for some minor eccentricities, pork pie-hatted Slim donned an ash-colored velour shirt while quivering through melodramatic sad songs, keeping tongue firmly in cheek during several impish curiosities.

Slim’s cracked bari-tenor, expressive if not rangy, brought a delicate chill to poignant allusions and a relaxed playful demeanor to milder sentiments. Prancing across the stage strumming fast jangled chords, he had the sanguine saunter of a salty troubadour, spitting exasperated verbiage and relating silly anecdotes when not busy fronting the bare-bone rhythm section (bassist Paul De Figlio and drummer Malachi De Lorenzo). He put on the gas face or wore a goofy smirk to squeeze more passion out of each whimsical piece.

A week later at Maxwells in Hoboken opening for Crooked Fingers (ex-Archers Of Loaf guitarist Eric Bachmann’s pensive solo venture), the skinny Semite, dressed down in guinea-t and casual gray slacks sans band, attempted fewer new songs, unleashing a short itinerary of older material. Adding rambling interjections and funny narratives to keep his repertoire fresh, Slim tries to never play originals the same way twice, much like mighty icon Bob Dylan. Yet Slim admits he could listen to AOR standards such as The Who’s Baba O’Riley (“teenage wasteland”) every day without hesitation. Plus, he gives respect to another well-known ‘60s Brit-rock crew, the Kinks, whose “Waterloo Sunset,” he adores.

“I think the Kinks deserve more credit. Ray Davies is the man, but I think he pissed off a lot of people.” Slim grins then remarks, “I was humming “Happy Jack” after hearing it on a television commercial and actually met someone claiming he didn’t like The Who. Who the fuck wouldn’t enjoy The Who?!!”

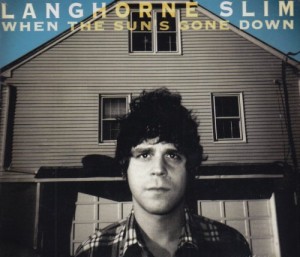

But despite his admiration for revolutionary post-Beatles archetypes, truth is, Slim’s Narnack Records long-play debut, When The Sun’s Gone Down, is indubitably informed by traditional Country blues, rustic bluegrass, and Dust Bowl era ballads instead of any weightier classic rock impetus.

But despite his admiration for revolutionary post-Beatles archetypes, truth is, Slim’s Narnack Records long-play debut, When The Sun’s Gone Down, is indubitably informed by traditional Country blues, rustic bluegrass, and Dust Bowl era ballads instead of any weightier classic rock impetus.

Spindly acoustic and expeditious banjo linger above bustling percussive beats on urgent love-struck opener “In The Midnight,” breezy affectionate gush “The Electric Love Letter,” and hokum organ-splashed hootenanny “Set Em Up.” Chiming pedal steel-aided adoration “Mary” and shuffling fiddle-ensconced “Loretta Lee Jones” maintain mint-y freshness. The latter recalls Buddy Holly’s zippier rocking snapshots while retaining a concise folk-y resonation.

Though oft-times lyrically obsessed with solitude, as per abrupt harmonica-fuzzed chant “And If It’s True” (‘I was alone but not lonely’), brusque lo-fi scruff “Drowning” (‘I’d kill to be alone’), and the scratchy tear-stained drifter’s lament “I Ain’t Proud,” he downplays any significant underlying defeatist attitude with restrained jocularity.

“I’ve been in a few relationships so I sing about the painful aspects, which is easier than sharing the happy parts,” he advises.

Akin to its humble back porch serenity, the sumptuously bucolic When The Sun’s Gone Down artwork appropriates suitably modest black and white dusky photographs.

Slim asserts, “The front cover features my friend Mike’s Jersey house. The back shot is from the house I grew up in. Inside, there’s a puzzle of the world’s strongest man, Louis Cyr, which my father, an amateur body builder, left in the basement when my parents split, along with the sailfish on the paneled wall.”

Nevertheless, when all is said and done, it is Slim’s pliable perspicacity of every man’s joyous wonders and, conversely, isolationistic defeats that seep deeply into the mind. And when an existing arrangement needs color splashed on for a cheerier mood swing, Slim goes and fetches accordionist Brendan Ryan to perk up verbose assurance, “Hope And Fulfillment.” In summary, he brings a greatened noble sense of integrity to a bygone generation’s most fertile ideals, whether ceding down and out allegories or rendering snugly devotional keepsakes.