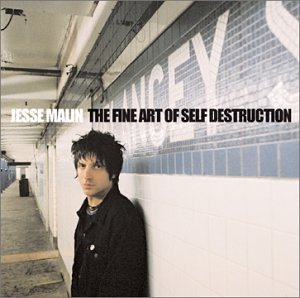

FOREWORD: New York mainstay, Jesse Malin, could talk your ear off. And that’s a good thing if you’re interviewing the ex-punk maven. After his hot local band, D Generation folded, Malin started drifting into comforting singer-songwriter fare. ‘01s The Fine Art Of Self-Destruction gained some aboveground acceptance, but ‘04s The Heat, ‘07s glam-deranged memoir, Glitter In The Gutter, and ‘08s covers LP, On Your Sleeve, never took that extra step to qualified national stardom. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Fast talking Queens native Jesse Malin knows what it feels like to have doors shut in his face, recording demos denied by sundry labels, and the best night of his life ruined. But he had the courage, patience, and perseverance to refuse quitting music until a miracle happened. It’s a mighty long road from the suicidal madness of “No Way Out” from his former band D Generation’s self-titled leathery punk debut to the urban angst of ‘96s No Lunch and the reflective retreat of their hard-to-find, third and final disc, Through The Darkness.

Writing lyrically profound songs during a slight tenure away from recording, Malin couldn’t get a break until drinking pal, well respected bard Ryan Adams, came to the rescue and offered to produce what became the stunning solo project, The Fine Art Of Self Destruction.

A toned down urgency affects sad, brooding fare such as the introspective “Queen Of The Underworld,” the sensitive acoustic ballad “Brooklyn,” and the dirgey, regretful title track. Cathedral-like piano adds resonance to Malin’s moaned discontent on the peaceful sedative, “Downliner.” But the bemused mood shifts to upbeat for the thoughtful “Almost Grown” and the beat-driven bass throbber “Wendy.” Throughout, his whined baritone goes from tearful longing to celebratory, evoking heartache and pain with the same yearning commitment given joy and redemption.

A toned down urgency affects sad, brooding fare such as the introspective “Queen Of The Underworld,” the sensitive acoustic ballad “Brooklyn,” and the dirgey, regretful title track. Cathedral-like piano adds resonance to Malin’s moaned discontent on the peaceful sedative, “Downliner.” But the bemused mood shifts to upbeat for the thoughtful “Almost Grown” and the beat-driven bass throbber “Wendy.” Throughout, his whined baritone goes from tearful longing to celebratory, evoking heartache and pain with the same yearning commitment given joy and redemption.

At a wintry Mercury Lounge show, Malin offered sentimental thoughts between each well-received tune. He recalled the thrill of achieving a lifelong dream opening for Kiss at Madison Square Garden being quashed by the masked marvels cruelty towards D Generation and the post-gig arrest for public alcohol consumption. He dedicated an acoustic turnabout to dead idol Joe Strummer and the as-yet-unrecorded “Arrested” to kiddie porn-charged Who legend Pete Townshend before petitioning war-bent Republicans with the timely Nick Lowe-composed Elvis Costello smash “What’s So Funny (‘Bout Peace, Love and Understanding)” for a blazing encore. Joined by veteran keyboardist Joe Mc Ginty, bassist Johnny Pisano, drummer Paul Garisto, and guitarist Johnny Rocket, Malin captivated the spirit and essence of his Adams-produced solo chestnut.

In the early ‘90s, D Generation was at the helm of the downtown St. Mark’s punk scene. I remember getting toasted with you guys at defunct club, Coney Island High.

JESSE: Scenes are great, but they only last a certain amount of time. People burn out, bands expand. You gotta get out of your little town. Every night was an unwritten party. Who knew what would happen or where we’d go. Are we gonna break these bottles and knock this bar over. It was decadent good fun. I missed the ‘70s pre-AIDS Max’s Kansas City and CBGB’s scene. D Gen wanted to relive what we missed as kids. We were exciting, scheduling drinking at bars we’d drink for free at. We got signed. Things got wacky with EMI. We went around the country, came back, there was a bidding war, and we went with Sony. It was like going to college with friends. I toured with people I grew up with and went to Europe. I knew the D Generation guys since I was 12.

But it was time to change. Musically, the last two D Generation albums had a Neil Young cover (“Don’t Be Denied”) and an acoustic song. Danny, the guitarist, and I, would sit on the bus listening to Springsteen’s Nebraska, old Elton John, Johnny Cash, Tom Waits, Pogues, and Dylan. It’s about songs. I wanted to do something besides playing faster, louder for the mosh pit. It’s more about the lyrics and music. It’s still not singer-songwriter moustache-slippers-pipe stuff. It’s still coming from a rock place. I got into roots music through the Rolling Stones, Replacements, Dylan. I don’t have a Waylon Jennings album, but I’ve always been into songs and attitude. Good rock and roll makes you wanna quit school, run down the street with friends, fall in love, break up with someone – just react. Bands like the Clash did a lot of things while keeping it real.

So I did the solo thing and made demos for friends. One was Ryan Adams, a D Generation fan I met in Raleigh, North Carolina. He decided he wanted to produce the record and I didn’t have much money. We made it in five days instead of six. Once he didn’t show up because he had too many Nyquils or milkshakes the night before. (laughter)

What did Ryan add to the sound?

He comes from the South. I’m from the urban North. We don’t sound alike. Unless you’re Jimmy Page, it’s good to have a producer. It focuses you to be objectively. I’ve worked with Tony Visconti, Rick Neilsen, and Ric Ocasek. It helps to have an editor. Ryan added to the charm. He did it fast live in one big room like a ‘50s Sun Session or Ramones record. We’d do warm-ups and he’d say, “That’s it!” I’d say, “I was just warning up.” He’d say it had so much feeling. I was pissed he was taking first takes. He’d go play pool and I’d record another track and he’d go, “What’s track 11? Fuck you!” and erase it. Later, we put it on at neighborhood bar, Manitoba’s, and I thought we’d captured a snapshot of New York. Not just the sound of winter after 9-11 but being in the city in the cold.

Did these imagery-laden reflections come together piecemeal?

Sometimes I’m drunk in midtown old-man-bars and like a wallflower I listen to people talking and scribble things on napkins, matchboxes. I listen to people talk on great films and hear a phrase, adjective, cliché. It’ll stick with me. Some fit into stories. I distance myself from being too personal or exposed. “Almost Grown” is the first half of my life almost verbatim. I stole the title from Chuck Berry.

“Almost Grown” deals with youth-oriented problems but carries an upbeat tone.

I like that duality. Sam Cooke is one of my favorite singers. He’s able to convey happiness and sadness in the same note. So there’s festive music with a sad story. When I do that song acoustic live real slow it fits what the song is about better.

“Wendy” contrasts your defeated baritone whine against fast moving bass-throbbing urgency.

It’s a road song about someone who bailed out that had good taste in music, movies, and books and took off and we have no sense why. You wonder if they lost their mind or haven’t the guts to communicate. He’s like a fugitive running away from a relationship, friends, and maybe, himself.

You and your sister struggled growing up with a single mother who died of cancer. On Self-Destruction, you mention sprinkling her ashes in the water.

I could relate to sadness, abandonment, isolation, being an outsider – things rock and roll helps medicate and save you from blowing your head off. These songs are exorcisms and a release. People say it’s dark and sad, but I see hope. There’s some light at the end of that subway tunnel. You get a community through the music scene and find ways to survive. Thank God there’s an alternative way of living. Not alternative like great bands Pavement and Primus, but in ways you don’t have to be in a typical town at college with a job or car.