FOREWORD: Since this ’99 interview with Stew of the Negro Problem, the colorful orchestral pop mastermind’s Passing Strange has won a Tony Award for Best Musical Book. He’s also released at least one Negro Problem record (‘02s Welcome Black) and two under his own name, Stew (‘00s Guest Host and ‘02s The Naked Dutch Painter). Unfairly confined to the underground (literally, I saw him play Knitting Factory’s basement space twice), Stew is a truly gifted tunesmith in need of better recognition. His constant companion for over a decade, Heidi Rodewall, always offers solid musical support. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

The Negro Problem’s Mark Stewart (a.k.a. Stew) and Heidi Rodewald (formerly of L.A. pop group Wednesday Week) recently showcased scaled down, dandy originals for five consecutive Wednesday’s in March at Tribeca’s Knitting Factory. Living temporarily in Brooklyn (maybe permanently if the rent is right), the dynamic duo emerged from the same Silver Lake, California, underground pop hotbed as Beck, the eels, and Wondermint.

By embellishing well-constructed compositions with distinctively Baroque pop influences such as the Beatles, Beach Boys, and Arthur Lee’s Love, TNP garnered great press and received cult status with ‘98s fabulous Post Minstrel Syndrome.

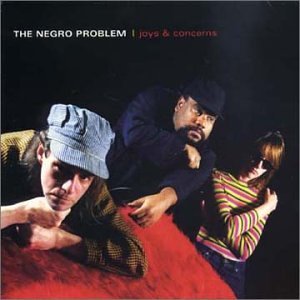

Two years hence, the revamped combo return with the retro-refined masterpiece Joys & Concerns (Ariel Flipout Records). Caught in a “crazy mixed up world” full of uncertain romance and self-doubt, Stew’s ambitious lo-fi fantasies gleam with emotional resilience while retaining a definite childlike dalliance.

Like an adolescent bohemian daydreamer, burly Stew drifts off into “Comikbuchland,” a lush, synth-soaked paradise clustered with Sgt. Pepper insouciance later re-cast as a snazzy, organ-fueled rollercoaster ride titled “The Rain In Leimert Park Last Tuesday.” On the sleek “Mahnsanto,” he visits Disneyland and sulks over Tomorrowland’s demise. Written from the perspective of a gay doll stuck sucking “Barbie’s plastic tits,” he confronts societal norms with the wry “Ken.” But the brightest jewel on Joys & Concerns has to be the tempo-and-mood-shifting, Magical Mystery Tour-derived “Goode Tyme,” a hook-filled trinket topped off by Stew and Heidi’s buttery dual harmonies.

Before loading Heidi’s keyboard into an associates’ car, then driving her and Stew to a late night, post-Knitting Factory-gig diner, I spoke candidly with them.

Why has Silver Lake developed such a keen pop scene?

STEW: I have no idea. There’s something about the area. It has always been an artistic area. In the ‘20s, there was Aldous Huxley. It must be something metaphysical, weird, or just cheap rent. Cheap rent attracts people who do interesting art. But I’m tired of L.A. We can pay rent but we want to move on and be a band that can play the whole country. That’s why we’re doing a Knitting Factory residency.

What artists initially inspired you?

STEW: The people who turned me on to rock and pop were black musicians who were very eclectic. The first time I heard Pink Floyd and progressive rock was when I was auditioning for an all black funk band at 14 years old. They accepted me into the band, lit up a doobie, and put on Dark Side Of The Moon. True musicians have open ears. The first time I heard Abbey Road was when my cousins played it the week it came out. It was a big event. So it wasn’t like I had to crossover. Back then you’d hear James Brown and Sly & the Family Stone next to the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Jethro Tull when radio was wide open.

How do most of your arrangements come about?

STEW: It’s not that thought out. It’s spontaneous. We try to keep ourselves awake when we’re making the music. (laughter)

“Goode Tyme” seems to sum up your own personal Joys & Concerns.

STEW: You hit it. That song was the defining moment of the record. But the d.j.’s in L.A. like “Comikbuchland,” the slow version. I can’t predict what they’ll like. It’s my favorite tune. On one hand, it’s totally sincere, and on the other, it’s sarcastic. It’s daring to be optimistic.

Do you find there’s a distinct difference between East and West Coast pop?

STEW: I know there was a difference between East and West Coast pop from the ‘60s. The current stuff, I don’t know. The world is so small regional is a concept that went away. But in the ‘60s, the Velvet Underground would have never happened on the West while the Beach Boys couldn’t have happened on the East. The West is more into harmony. The East is real fast. That’s why you get the urgency of the Velvet Underground, Television, or even doo-wop. Whereas, the West Coast artists take it slow and sit around in the garage. I know a guy who would see the Beach Boys when they rehearsed. They’d just sit around in the gym all day.

How’d you hook up with Heidi for Joys & Concerns?

STEW: We needed a bass player who sang. She was in Wednesday Week and had been to the mountaintop. She had done the MTV nationwide tour. She lived up with a friend of ours, learned the songs, and that was it.

How does Post-Minstrel Syndrome compare to Joys & Concerns?

STEW: The second record has someone who has had relative difficulties and pain. It wasn’t supposed to be sad, but the realities crept through. It’s more adult. I had the guts to write about what sucks. Before, I never wrote about problems. I didn’t want to whine and cry about my shoes like Eddie Vedder does while he’s got a million dollars. I’ve had a good life, but things got weird relationship-wise. The first album was like being in the playground, having fun and laughing.

Why are Joys & Concerns’ more upbeat tracks near its conclusion instead of up-front like most pop records?

HEIDI: Everything was against the sequencing. But I was listening to Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions and I thought it was cool how it came down really fast for a low key second song (“Visions”). Besides, we’re not for the kids. That’s not our audience.

STEW: But you can’t fault the kids. When we were doing Joys & Concerns, this 16 year old boy whose father is the station manager of KRLA and has a wealth of knowledge about pop and access to all the right music was asked ‘Why aren’t you into music? You like video games’ The kid goes, ‘Do you really fucking expect me to get excited about Matchbox 20?’ His dad was like ‘case fucking closed.’

There’s this massive conservatism that’s choking this country and its mass marketing of boring, contrived music.

STEW: Kids don’t like pop music anymore. 12-string guitar Beatles-influenced stuff had a brief period, but now kids like more ballsy stuff. Kids are far removed from pop. My eight year old daughter has only been listening to TNP, Hanson, and “Macerena.” When she heard the Beatles’ White Album she said, ‘Is that you guys?’ Her friends have no music that sounds remotely like “Blackbird.” When she hears verse-chorus-verse-chorus-fade, she thinks it has to be TNP. It just shows that this way of structuring music is totally lost. We’ve played outdoor shows at Santa Monica on Saturday afternoon to wide open demographics. Everyone is there: backward hat skateboarders, rappers, intellectuals with John Lennon glasses, and old ladies. When we play, the kids stop and listen, then walk away. There’s nothing in our music that grabs them. But there’s the guy with the glasses who has come out of Borders Books who lets the music grab him by the throat.

Take “Livin’ La Vida Loca.” It’s like a taco commercial. There’s no subtlety. It’s desperate sounding. The production makes sure you can’t take your attention away. Nothing lets you off the hook for a second. I’m trying to get my kid to listen to the Beatles and other stuff just to indoctrinate her. The way things are now, I hate the fact Top 40 sucks. I love the idea of a #1 song, but Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey are histrionic divas who don’t sing songs which exhibit their entire range. Why can’t they record an Aimee Mann song which has some depth?