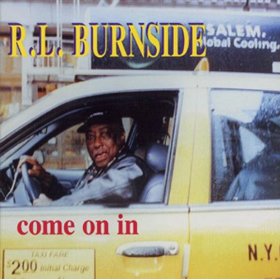

FOREWORD: R.L. Burnside was a good-hearted Delta bluesman whose career was revived when dedicated Oxford, Mississippi label, Fat Possum Records, began putting his creaky bare-boned guitar-based blues into contemporary rock and techno settings. His most approachable LP for newcomers may be ‘99s Come On In. I spoke to Burnside at this time. Afterwards, he released ‘00s fine Wish I Was In Heaven Sitting Down and ‘04’s Bothered Mind. A year later, he died from complications due to a heart attack. This article originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Along with the recently deceased Junior Kimbrough and the still viable T-Model Ford, rural Mississippi blues singer-guitarist, R.L. Burnside began recording for Matthew Johnson’s tiny contemporary label, Fat Possum Records, as a senior citizen. Despite being in his seventies, the revitalized Burnside remains a vital link to traditional pre-World War II blues. He tours constantly and during the ‘90s has dropped critically acclaimed long-players Bad Luck City, Too Bad Jim, A Ass Pocket Of Whiskey (with blues-y punk renegades Jon Spencer Blues Explosion), Mr. Wizard, and the just-released Come On In.

Extending the cryptic heritage of Delta bluesmen Fred Mc Dowell, Bukka White, Son House, and Robert Johnson, the experimental Burnside reluctantly, at first, took backwoods folk-blues down a courageous new path by imposing his stripped-down primal songs with ‘90s electronic technology. By acquiring a considerable reputation in post-alternative rock circles, Burnside has helped expand the once impenetrable boundaries of historic Mississippi hillbilly folklore to an otherwise completely removed audience.

Featuring grandson Cedric Burnside (drums) and Kenny Brown (guitar), Come On In continues to flexibly integrate the old with the new. Over simple, repetitive riffs and rustic beats, Burnside’s stoically scraggly baritone conveys gut-level emotions dripping with juke joint passion and chilly swamp-rooted raunch.

While most septuagenarians are too set in their own ways, Burnside stays relatively fashionable by trusting artists less than half his age to juice up his primal musings. German techno-hardcore maven, Alec Empire, remixed the fervent “Heat”; producer Tom Rothrock programmed the discofied version of “Rollin’ Tumblin’” and the spooky reverberation, It’s Bad You Know”; and Beal Dabbs added clavinet and organ to the clustered “Don’t Stop Honey.”

I spoke to Burnside via the phone in January, 1999.

Tell me about the records you made before Fat Possum came knocking.

Tell me about the records you made before Fat Possum came knocking.

R.L. BURNSIDE: They’re not that different except maybe the singing.

Did you originally sing Gospel before reverting to traditional blues like many artists do?

R.L.: Yes. I was singing spirituals in the church with my sisters. I learned to play guitar by picking it up from Fred Mc Dowell and Randy Barnett.

Gospel purists once considered the blues to be the devil’s music. Did you?

R.L.: No. I feel the Lord entitled me to sing the blues.

Then why don’t you touch upon religion in your songs?

R.L.: I think playing the blues is about feeling. See, the blues came from slavery times and spoke about what people were feeling. You couldn’t tell ‘the man’ what you wanted to, but you could sing about it, you know. And if you got a woman and somebody takes her, you got the blues. If you drive up to your house when you’re married at about 2:30 in the morning and get out of the car and meet your cat comin’ out of your yard, and you hear, ‘heel, heel,’ you got the blues.

Was there radical hatred when you were growing up in the heart of Mississippi?

R.L.: There was some, but it wasn’t that bad. It’s a whole lot better now. You can go anywhere you want to. Back then, when I was getting raised, you had to go in through back doors. But now a lot of white women are married to black men and black women are married to white men. It’s all around.

Songs like “Don’t Stop Honey,” Come On In (Part 2),” and “Heat” deliberately introduce technical wizardry to rural blues in a groundbreaking manner. Did you initially balk at having your traditional songs electrified and remixed?

R.L.: I didn’t think much about doing it, but the record company said they wanted something like the Jon Spencer record (A Ass Pocket Of Whiskey). I said all right. At the time, I didn’t like the mix. Then it sold so well and I like it now. And more young people come to my shows now – people who would have never seen me. The first place I played with Jon Spencer, a guy asked me, ‘Have you ever played with these guys before?’ I said no I hadn’t. So he bought me a package of earplugs and said, ‘You’re gonna need these. They play loud.’

You also mix in strict folk-blues like “Just Like A Woman.” Was that done in one take?

R.L.: That’s a song from the hills, and I think it was done in one take. It’s something like a boogie, you know.

How has the live music scene changed in Mississippi since the ‘40s and ‘50s?

R.L.: Now everybody be in their partying. Now there’s more white people than blacks. A long time ago, there’d be only black people at the house party.

Is the county in which you live as poverty-stricken as it was during the ‘60s?

R.L.: No. It got a whole lot better. After Martin Luther King died, it made times better for us.

I read in an article that you have 13 children with 11 different women. How could you afford to feed and clothe them?

R.L.: Well, one died in a car accident about 10 years ago. I worked on a plantation, did commercial fishing, drove concrete trucks and containers. Once or twice a year, I’d have to do extra work. 12, 14 years ago, I got where I could make a living out of playing music.

What’s the difference playing US clubs as opposed to European ones?

R.L.: They like the blues more in Europe because they ain’t heard it as much as Americans. They’ve heard it on tape, but haven’t seen it live too much. And I think they like it good. The places be sold out a lot of times. When I first went over there, they were hollering when I came out to play. I asked someone, ‘Why do they like the blues so much when 90% of them can’t speak English?’ He said, ‘They just like the rhythm.’