FOREWORD: Whenever you get the chance to interview an iconic band at the peak of their powers, you’re a lucky man, even if you’re a band hound such as myself. So when the chance came to talk with co-composing Sonic Youth drummer, Steve Shelley, I was happy as a pig in shit. After all, Sonic Youth enviously inspired two trademark generational scenes of historic proportions: England’s ‘80s shoegaze spectacle and ‘90s grunge mania. Relying on noisily distorted guitar disruptions, these no wave free-Jazzed navigators hit shimmering feedback-scraped heights then crashed and burned like the space shuttle.

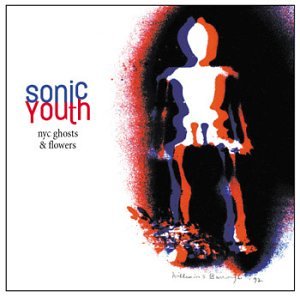

The following piece was done in 2000 to promote NYC Ghosts And Flowers. ‘02s 9-11-affected elegy, Murray Street, and ‘04s Sonic Nurse merely sufficed, but ‘06s sturdily brawny Rather Ripped and ‘09s The Eternal struck back with lethal venom. Check out Thurston Moore interview for more SY stuff. This article originally appeared in Aqurain Weekly.

Extending the short-lived legacy of late ‘70s subcultural Bowery ‘no wave’ deconstructionists DNA, James Chance & the Contortions, Glen Branca, and Lydia Lunch further than anyone could have possibly foreseen, Sonic Youth were one of the most important, influential ‘80s bands (still thriving to this day). More astoundingly, the Bowery quartet inspired the entire Seattle grunge movement, introducing their atonal distortion (‘white noise’) to the Melvins, Nirvana, and Mudhoney.

By continuously exploring outer boundaries of freeform rock and slipping into minimalist Jazz territory at will, Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore (guitars-vocals), his wife, bleach-blonde dark temptress Kim Gordon (bass-guitar-vocals), Lee Ranaldo (guitar-vocals), and Bob Bert (drums) radically tore down conventional rock limitations.

After a few formative EP’s and albums, 1984’s Bad Moon Rising combined chaotic feedback with grating dissonance, forming fully jagged, dirge-y mantras.

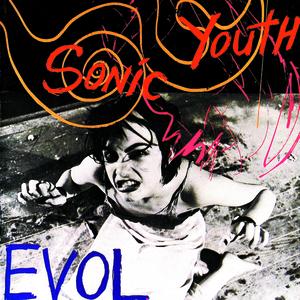

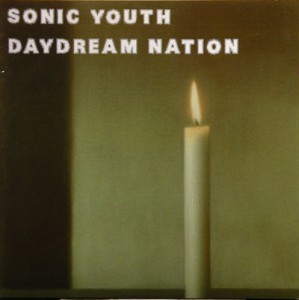

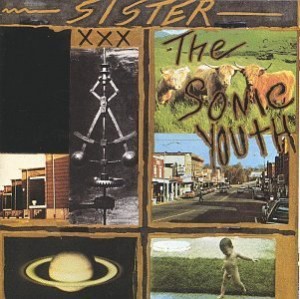

Tired of touring, Bob Bert quickly exited. Steve Shelley took over drum chores for the twin pillars of strength, ‘86s menacing Evol and ‘87s similarly-themed Sister. These records provided the claustrophobic anxiety and lethal guitar shrapnel anchoring ‘89s triumphant Daydream Nation.

When Geffen records signed Sonic Youth, the investigative art-damaged Lower East Side bohos responded to major label accessibility with one of their least viable (and somewhat directionless) albums, Goo, a flawed gem which informed Dirty, its more feverishly powerful follow-up. ‘95s Experimental Jet Set, Thrash, And No Star loosened their spontaneous free Jazz impulse, while modern classical gestures crept into Washing Machine and the autumnal A Thousand Leaves.

Produced by post-rock instrumentalist Jim O’Rourke (Stereolab, Superchunk), ‘00s NYC Ghosts And Flowers markedly broadens the bands’ already wide scope, stretching into spoken word inspired by late ‘60s/ early ‘70s Cleveland radical freak drug poets. The late American poet, D.A. Levy inspires Moore’s freestyle rants on the fragmented guitar collision “Small Flowers Crack Concrete,” while the implosive “Stream X Sonic Subway” could pass as suspenseful beat poetry.

Ranaldo’s half-sung ramblings detail Big Apple woes above the increasingly intensified, repetitive, detuned guitar plink of the title track. Gordon’s cool detachment and seductive moans bring a coarsened urgency to “Nevermind (What Was It Anyway)” and her hushed, monotone, one-word thoughts spew across the eerie desolation of icy deluge, “Side 2 Side.” The cacophonous “Free City Rhymes” and cryptic death knell, “Lightnin’” bookend the adventurous disc with expectant freeform scree.

Before heading to France to record with French artist, Bridget Fontaine (Gordon’s favorite singer), I spoke to Sonic Youth timekeeper, record label entrepreneur, and Hoboken transplant Steve Shelley about his influences, the sprawling conceptual homage to minimalist composers called Goodbye 20th Century, and of course, NYC Ghosts And Flowers.

Do you see this album as an extension of A Thousand Leaves?

Do you see this album as an extension of A Thousand Leaves?

STEVE: Well, it’s the next one. (laughter) It’s a departure in a way, but there are similarities. They’re recorded in our home studio in New York City.

Many songs deal directly with the Lower Manhattan vibe.

STEVE: Yeah. It’s definitely more urban while A Thousand Leaves was a bit more countrified, if you could imagine that. It was more lush and relaxed, while this one is a bit more uppity. We worked with producer Jim O’Rourke on Goodbye 20th Century and NYC Ghosts And Flowers. He brings out different elements of the group that wouldn’t happen otherwise. He’s a real instigator and a fun guy to throw ideas off of. He’s up for anything.

Since you grew up in Michigan, were Iggy & the Stooges and MC5 major inspirations?

STEVE: No. I was too young for all that. They were from a generation before me. I didn’t hear of them until I left Michigan. I listened to commercial FM radio. The closest I got to the MC5 was Ted Nugent and Alice Cooper. But I grew to appreciate their stuff later on.

Do most of Sonic Youth’s arrangements come from improvisations or melodic clusterfucks?

STEVE: It’s actually both. A lot of it’s just jamming to see what sticks. Because we have a rehearsal room/ recording studio, we could go in to roll tape and collect ideas. Sometimes Thurston will come in with a chord progression and we’ll start adding to it. I love going to different studios since they have their own separate atmosphere, but it’s great to have your own place and not be on the clock.

I’m especially intrigued by the colossal magnitude of the title track.

STEVE: That’s directly inspired by the sessions to Goodbye 20th Century. On that album, there’s one song that starts quietly, crescendos for four-and-a-half minutes, then reaches its peak and gets quiet again. It’s an exercise in dynamics and what could happen within that.

Are you ever afraid your expansive arrangements may lose some potential listeners?

STEVE: I guess you could ask that of free Jazz artists as well. I don’t think we’re worried about that. We want people to listen, but we’d be selling ourselves short if we started listening to those ideas. It’s difficult enough having four different people with four separate ideas trying to meld something together.

“Lightnin’’ seemed inspired by Miles Davis’ early ‘70s albums Bitches Brew and Jack Johnson.

STEVE; Wow. I love that Jack Johnson record. That song was just an exercise in freedom. Kim gets to play trumpet and I play the electric groove box. That’s just the four of us going at it in the studio. We were going to bookend the record with two versions, but decided on one. The one parameter we set up for this record was we weren’t going to make a long 60-minute record like A Thousand Leaves. There are so many distractions. It’s hard to sit down and concentrate on a 70-minute disc. People have to learn to edit themselves and put out 30-minute discs.

What was it like getting selected to replace Bob Bert in Sonic Youth?

STEVE: I was checking out New York. I wasn’t sure I was going to stay. A friend and I were subletting Kim and Thurston’s Lower East Side apartment while they were on tour with Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds. I was wondering how I’d fit in. When they got back, they didn’t even ask to audition. I just joined the group. It was amazing. I got to tour with one of my favorite artists, Neil Young. It’s amazing how new and different things keep happening to us. Tomorrow, I’m going to Paris with the group to record with Bridget Fontaine. With all the renewed interest in French music and people discovering Serge Gainsbourg, it’ll be a trip to meet her.

Who are some of your favorite drummers?

STEVE: My first influences were typical. Ringo Starr, Keith Moon, Charlie Watt, and the king of drummers, John Bonham. When I play, though, I’m thinking about the song and trying not to overplay. I’ve tried to go in a minimal, understated direction lately. Some of that comes from my work with Cat Power and my own band, Two Dollar Guitar – being as skeletal as possible. I love Jazz drummers, too. But my initial influences were classic ‘60s rockers.

What’s up with your underground supergroup, the Wyldde Ratz, which includes guitarist Ron Asheton from the stooges, Mike Watt, Mudhoney’s Mark Arm, Thurston Moore, and Sean Lennon? Was it formed only to provide a song for the glitter rock soundtrack of the movie Velvet Goldmine?

STEVE: We recorded enough stuff for two albums. Originally, London Records was going to put it out. But I guess the soundtrack didn’t do as much business as expected. They paid for the recording, but they didn’t want to put out an LP yet. It’s funs stuff. Ron Asheton sounds amazing. We did some Stooges covers. Ron and Mark Arm wrote some songs together. It’ll see the light of day somehow. It’s pretty much down and dirty Detroit City Rock.

Did you ever consider Sonic Youth to be an extension of Jazz-rock pioneers King Crimson or Soft Machine?

STEVE: That’s probably the music I’ve heard the least of until recently. Thurston’s more familiar with that music. Interestingly, Gary, the drummer from Pavement, who was older than anyone in the band and was more of a hippie would always come up and say to us, ‘You must listen to a lot of Yes music.’ I didn’t know what he was talking about until the movie Buffalo 65 came out last year. I heard some amazing Yes music and understand what Gary meant. Robert Fripp and King Crimson had freedom and a certain awareness of other music, even though they didn’t adhere to rock structure, or sound like the pop-rock that was going on.