FOREWORD: I made quick friends with Thermals front guy, Hutch Harris, at Mercury Lounge supporting fantastic ’03 debut, More Parts Per Million. We conducted a weed-hazed interview in my wife’s van with then-member, Ben Barrett, while Harris’ paramour-bassist, Kathy Foster, worked the merch table.

Afterwards, I called Harris at home for an ’09 interview promoting the equally fine Now We Can See. Then, I caught the Thermals headlining Bowery Ballroom, spending a few minutes prior to the show laughing it up with Kathy, her brother, a publicist, and finally, Hutch. Both following interviews originally appeared in Aquarian Weekly.

Just east of Portland, Oregon’s downtown district across from the winding Williamette River and past its Industrial banks lies the bucolic region indie-minded combo, the Thermals, call home. Capturing the energetic vitality of reckless post-collegiate uncertainty, these scruffy erudite rockers bend muzzled vocals, durable rhythms, and clanging distortion into crudely skewed 2-minute-per-song efficacy.

Live at NYC’s Mercury Lounge, elastic Thermals frontman Hutch Harris spews perceptive literary-bound lyrics in a spastic sputter while restlessly limbering across the stage. Bespectacled ex-girlfriend Kathy Foster dexterously plucks her bass, supplying plenty of punch. Bald, skullcap-wearing guitarist Ben Barnett (of 4-track minimalists Kind Of Like Spitting) nervously jerks his head up and down to the punctual beat, sweat pouring down his prominent forehead as he rips at the axe with feral determination. Behind the kit, Jordan Hudson slashes away mightily, pounding skins and bashing cymbals with hands flailing wildly in every direction.

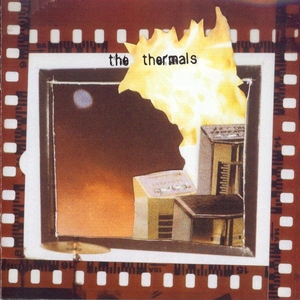

On the Thermals blazing 27-minute/ 13-song debut, More Parts Per Million, lo-fi production belies jittery roughhewn morsels scrappy enough to induce spiky-haired punks and musty garage fanatics alike. Like a paranoia-stricken Drill Sargent, Harris barks out commands above the perfectly frenzied tension of “It’s Trivia.” The dismissive “No Culture Icons” wittily destroys false ideals, as Harris excitably scurries his way through the twisted obfuscation of the slobbered couplet, ‘hardly art, hardly starving/ hardly art, hardly garbage.’ While the swiftly swaggering “Born Dead” invites comparisons to the Strokes on speed, the scuzzy urban grit of “My Little Machine” obliviously collides virile Jon Spencer Blues Explosion acrobatics with The Cure’s Goth-glam gloom.

On the Thermals blazing 27-minute/ 13-song debut, More Parts Per Million, lo-fi production belies jittery roughhewn morsels scrappy enough to induce spiky-haired punks and musty garage fanatics alike. Like a paranoia-stricken Drill Sargent, Harris barks out commands above the perfectly frenzied tension of “It’s Trivia.” The dismissive “No Culture Icons” wittily destroys false ideals, as Harris excitably scurries his way through the twisted obfuscation of the slobbered couplet, ‘hardly art, hardly starving/ hardly art, hardly garbage.’ While the swiftly swaggering “Born Dead” invites comparisons to the Strokes on speed, the scuzzy urban grit of “My Little Machine” obliviously collides virile Jon Spencer Blues Explosion acrobatics with The Cure’s Goth-glam gloom.

Despite random similarities to Steve Malkmus, such as your facial structure, literary acuteness, and shared hometown, I find it difficult to compare the Thermals lo-fi savagery to his esteemed ex-band, Pavement.

HUTCH: I have Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain and Slanted & Enchanted, but they weren’t a band I had real affection for. I’d never put them down. I’m a tall skinny white guy with brown hair like him. I’ve served him lattes at a coffee shop hipsters frequented.

Do you enjoy literature?

HUTCH: Music was my third passion. First was writing, then acting. But music, you have the most control over and the most freedom to be what you want to be. Writing and acting are confining, because you’re using what someone put before you. But I don’t want lyrics to come across literary. Bad Religion’s lyrics end up alienating people because they’re posing themselves as teacher. I don’t want to sound preachy. I’m a Hunter S. Thompson, Kurt Vonnegut fan. Joseph Heller, George Orwell – really classic universal stuff. When you’re writing as a youngster, you’re re-enforcing the fact you’re a nerd and have trouble in social situations. Whereas in music, even if you suck, you’re in a band getting cool girl action. Writers don’t get the superficial benefits of being in a band.

Ben, what are your influences?

BEN: The same things that knocked me out as a kid is what knocks me out about the Thermals. If I was 16, I’d say Sepultura, Dark Angel, Forbidden, early Anthrax. At 18, the Smiths, REM, Samiam, Dinosaur Jr., Jawbreaker. Now, at 27, I realize there’s an energy that drove me to those bands – The Descendents, Drive Like Jehu. Stuff I go for as far as guitar aesthetic is the Buzzcocks, Joe Jackson, Elvis Costello, because you have to have a big right arm and go for it. For the melodies, I go to Phil Ochs, Leonard Cohen, the Mountain Goats.

How’d you two hook up?

BEN: At a New Years Eve party at Hellgate House. I remember Hutch and Kathy were in Urban Legends. Kathy sat down at the drums, I looked over at my friend, and said, “Who the fuck’s that?” Hutch was someone I admired but I was weirded out that he liked me. All four of us could play each other’s instruments. Jordan’s got a recording project, Opera Cycle. We came together to do something simpler, more streamlined. We each concentrate on one thing. Jordan knows his way around countermelody in a rad way. He’s an amazing vibes and piano player, drummer, and singer. He’s the hidden talent.

HUTCH: The secret weapon, the shining star.

The Thermals music is too fast to be arty like the Talking Heads.

HUTCH: I like that we’re not arty. It’s the same as the lyrics not being too literary. I feel it’s alienating if the audience thinks you’re too smart or too cool. Keep it simple.

Don’t be contrived.

BEN: Yeah. The idea is to know what you could pull off. If I see a band that looks supercool, I might not find them pretentious if they actually pull it off. Otherwise, you won’t buy it.

HUTCH: I think I know my limits. I know I’m not the cool guy ‘cause that’ll just look stupid. So if I be myself, stay nerdy and spazzy, that’s fine.

The Thermals capture that pure, wet-behind-the-ears, youthful indiscretion well. Production lacks, lyrics sound fuzzy, but the feeling is right.

HUTCH: Totally. We’re not naïve, but we’re innocent in some ways. We’re not 19 going out for the first time.

BEN: We know how shows go, how they’ll progress, and we’ll be fine with it.

HUTCH: We’ve met dads at all ages shows that tell us we make them feel young again. The best compliment on tour is older people saying we’re refreshing.

BEN: Nothing’s worse than a band coming out saying they’re gonna save rock and roll.

The Hives and Datsuns insinuate that, but they’re being cheeky with their brawny arrogance.

HUTCH: If you like that, it’s fine. But it’s not garage. The Hives record is huge, crisp, clear. That’s fine. But it’s not garage, and neither are the Vines. I could see how the Strokes are garage, but the Vines are just a radio band.

I like the deceptive idealism conjured on “No Culture Icons,” whether or not it has deep meaning.

HUTCH: The greatest thing about this record is the songs were written off the cuff without knowing Sub Pop Records’d pick us up. It’s terrible to recycle yourself as you make it, but since I wasn’t thinking anyone would hear it, I didn’t give a shit. That gave me the freedom, when I was writing, to have no self-reference. That’s why everything after the first verse is hypercritical, railing against everything the song goes for. But you start the song by talking about yourself.

BEN: I thought you wrote it from a critic’s perspective criticizing your work up to that point and you’re blowing up at them.

HUTCH: I feel we’re surrounded by mediocrity in Portland. There’s good and bad stuff, but somehow no one’s going for it. So it’s a criticism of that. But I’m humble enough to say I’m just like them.

What Portland bands do you like?

HUTCH: People go out to see the Swords Project – instrumental with some singing and post-rock soundscapes. 31 Knots people are into. They keep getting better over five years. Karate makes extra math-y deconstructions. People going to Portland shows complain nobody’s dancing.

BEN: That’s because nobody’s giving it to them the way Iggy did, the MC5 did, or the Sex Pistols did. That’s just punk. You could look at any genre and what bands kicked my ass – Forbidden or Braid, all very different crews with a raw essence of greatness that makes you move. That’s how hip-hop beats rock in many respects. It’s more about the people. That’s why Bjork is so amazing. Her records blink at you. There’s lot of popular bands that look and sound fine, but are they great bands? We’re trying to be.

—————————————————————–

THERMALS PLAY DEAD ON ‘NOW WE CAN SEE’

THERMALS PLAY DEAD ON ‘NOW WE CAN SEE’

Coming out of the Pacific Northwest indie rock scene fully formed, the Thermals mainstays, singer-guitarist Hutch Harris and bassist Kathy Foster, received paltry exposure in a folk-y boy-girl duo (annoyingly labeled twee-pop), a few unheralded combos, and surprisingly, a long-defunct stoner rock outfit. But as the Thermals, the now-married duo (plus several semi-popular local musicians) stormed the weighty underground scene in 2002 with a roughhewn, sometimes muffled, homemade cassette recording legendary Seattle grunge label, Sub Pop Records, saw fit to release in its primal, unfinished state.

Hitting the ground running with crudely sketched debut, More Parts Per Million, the Thermals’ charmingly upbeat two-minute drills came across as itchy, twitchy epistles just far enough removed from emo-core melodramatics to advance their self-described ‘post-power pop.’ Hutch’s brashly blurted shout-outs and demonstratively flailed riffs outshone the greener competition, gaining his band national attention. “No Culture Icons” captured all the pent-up frustration of a starving artist trying to find an audience willing to move beyond trendy MTV mediocrity. Searching for safety in an “Overgrown, Overblown” universe and hoping to survive past springtime in “Back To Gray,” Hutch’s clanging jingles resembled a cataclysmic cyclone slamming the shoreline. And his unkempt, whiplash 6-string prowess proved menacingly exhilarating through and through.

Benefiting from proper studio production without sacrificing the manic energy of their stripped down precursor, ‘04s Fuckin A dissects and bisects human suffering. An unmistakable furor extends from its bleak nuclear power plant cover art to its disgruntled subversive passages. Hutch’s best vocal performance adorns full-fledged rock anthem, “How We Know,” his most clear-headed, vibrant, provocative, and absolutely heartfelt pledge yet.

He toys with late-‘70s ‘oi’ punk yelping on ascending decree, “Our Trip,” answering the Sex Pistols urgent “Anarchy In The UK” plea with the same vigilance given venomous desecration, “Here’s Your Future,” the gloom-shaken highlight from ‘06s post-apocalyptic manifesto, The Body, The Blood, The Machine. A benchmark third album hosted by a blindfolded Jesus in second coming stance, The Body’s brassy romp, “An Ear For Baby,” and aggressive fuck-off, “Keep Time,” beg for a ‘new first world order’ away from America’s oppressive regime.

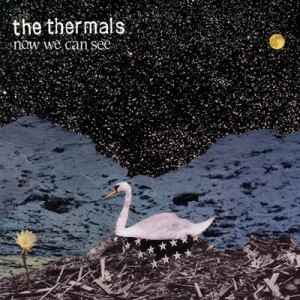

And then… the Thermals spoke from beyond an assumed grave (with Say Hi drummer Westin Glass now onboard), returning poised and readied to battle once more on ‘09s eulogizing Now We Can See (ironically, on Kill Rock Stars record label).

And then… the Thermals spoke from beyond an assumed grave (with Say Hi drummer Westin Glass now onboard), returning poised and readied to battle once more on ‘09s eulogizing Now We Can See (ironically, on Kill Rock Stars record label).

A parched afternoon setting can’t hide the hailstorm force of opening sepulchral proclamation, “When I Died.” Then, brazenly savage memento, “We Were Sick,” distinctly contrasts torturous teen angst against the joy of being high – its hooky chorus only overmatched by the instantly contagious title cut. Ranted testimonial, “When We Were Alive,” and hard-driving garage rocker, “When I Was Afraid,” hearken back to Detroit’s gloriously heady late ‘60s dynamos, the MC5 and the Stooges. And perky abrasion, “You Dissolve,” gives these nihilistic teasers an obvious dust-to-dust epilogue.

Even in faux-death, Hutch and Kath’s resolve remains intact. After all, a much-awaited resurrection was definitely in the cards. Far from actual extinction, the Thermals are now at the top of their game.

So, you haven’t lost your piss and vinegar even though your man, Obama, was elected.

HUTCH: True. But we wrote it before Obama was elected so we thought we were gonna soundtrack the first four years of Mc Cain-Palin.

Now that the Republicans have lost the White House, how will you continue to compose cantankerous political missives?

HUTCH: We’ll have to move beyond politics. We were already trying to but it kept creeping back in. We’ll have to find something new to whine about. A lot of our songs are about arrogance. And they’re arrogant themselves. Usually it’s a metaphor for humanity. We’re looking back on life and the history of people on earth who are arrogant, violent, and stupid. Our songs try to reflect that. The songs celebrate fucked up things. It’s not just to get down on everything.

On “Now We Can See,” you go from Garden of Eden to junkyard of debris, but there’s a happy chanted chorus.

On “Now We Can See,” you go from Garden of Eden to junkyard of debris, but there’s a happy chanted chorus.

HUTCH: Totally. We got to have a good time even if the world’s going to shit. Usually the songs we work on the longest and hardest, people think, ‘That’s just OK.’ But the things we just throw out there work better for us.

What were the most difficult tracks to complete?

HUTCH: “When I Died” had a lot of lyrical re-writing and editing. But then you have a song like “When We Were Alive” which I sat down and wrote from start to finish and didn’t touch afterwards. That was the first song written for the record and truly got us started – the whole ‘we were alive and now we’re dead’ concept.

“Liquid In Liquid Out” seems to remark upon the adage ‘garbage in/ garbage out,’ but in a stinky urinary manner.

HUTCH: When we were recording with John Congleton (Modest Mouse/ Explosions In The Sky/ Polyphonic Spree producer), he turned to me after that song and said, ‘That’s really disgusting.’ I said, ‘Thanks.’ That’s not really what I had in mind but we wrote a lot of this out on the Oregon coast and it was constantly pissing rain on us. So it makes sense there’s so much liquid on this record. We also had the most snow here in 50 years.

I see you as an underrated melodic guitarist stuck in indie-land with Matthew Sweet or Ted Leo. Who would you list as under-recognized axe slingers?

HUTCH: I’d put the Strokes’ Nick Valensi in there. He has some real good melodic songs. Kim Deal for her ‘90s Breeders stuff more so than what she’s doing these days. Last Splash and Pod are two favorite records – hard to top.

Who are some early influences?

HUTCH: The obvious one is the Ramones – that bubblegum punk angle with no blues riffs – just really major chords. Kath and I were raised in California’s bay area so Green Day were massive. The Pixies, of course. It doesn’t show in our sound, but I especially like the second wave of punk – Minor Threat, Subhumans, Exploited.

How about literary influences?

HUTCH: I don’t consider myself as that much into literature. But some writers are big for me, like Joseph Heller, Catch 22 and Something Happened. Hunter S. Thompson was huge. He’s the most influential on my early lyrics and the attitude – celebrating the world’s problems instead of complaining about them. And getting real high.

You’ve moved from the simple catchphrase stanzas of the debut to fully drawn-out verses.

HUTCH: It was intentional at first to write off-the-cuff and do no editing. I’d sit on my porch, write the song, come back inside, sing it, and it’s done. The first record was supposed to be about writing a verse, repeating it, and use very few choruses. I look at it as cheap poetry. Nail something into listener’s heads and repeat it. That’s what makes a catchy song. For Fuckin A, I wrote most lyrics while touring. We made a real effort not to slow down at all or think too much. Many bands eat shit on their second album so it was really a chance to move super-quick. We recorded it in three days. I don’t think it was our best record, but it was immediate. It was supposed to be a good, quick follow-up that didn’t lose any steam. As we went on, The Body, The Blood, The Machine was about taking that beyond, writing stories with an arc that’d be smarter. The lyrics were a good way to challenge myself. We’re kids from the suburbs. At first, we hated being called punk. It made us feel like posers. If you put on our songs, you’ll find it’s not mohawk-and-leather-jacket punk.

Are you railing against tyranny on The Body, as per the line, ‘I might need you to kill’?

HUTCH: It’s defensive. The lyrics are about escaping the clutches of a fascist machine out to get us. It’d be in justified self-defense.

There’s a continual struggle between existentialism and religiosity throughout your works.

HUTCH: I’m more existential. The new record reflects that even more. Kath and I were brought up Catholic. I was a good Christian ‘til I left high school and fell out with the church. The Body had a lot to do with what went on in the Bush administration and church and state. That got into this whole fantasy of its overall plot.

You enjoy ironic satire, don’t you?

HUTCH: Totally. It’s real important to keep it sarcastic and humorous. Many bands take themselves too seriously and it’s laughable. We’re saying what’s on our mind, but not to get on a soapbox – just to talk shit. That’s punk. Lyrically, I’ve had a natural progression. With guitar, I have to bust my nuts. I’ve played for 15 years but it sounds like it’s been five. I’ve never been a virtuoso and I’m always fucking up my solos live.